20,000 lives that mattered

Last summer, I wanted to “defund the police.” The more I've learned about the realities of policing and murder in America, the more I've come to regret it.

Around this time last year, protests for racial justice were swelling in response to the death of George Floyd. When the video first hit the news, I was angered and saddened. But having heard this story dozens of times before dating back to Trayvon Martin and Eric Garner, I cynically did not expect anything to change. As days passed, it genuinely surprised and confused me when it seemed like this time was different. Maybe it was the particularly heartless way that Officer Chauvin ended Floyd’s life; maybe it was the paradigm shift of Covid that led Americans to viscerally realize we were all systemically connected—whatever it was, voices that had long advocated for dramatic societal change were finally being listened to. I’d been loosely aware of movements to abolish prisons or policing; while restorative justice approaches seemed like an appealing alternative or supplement to our archaic and inhumane prison system, eliminating the police wholesale seemed radically outlandish. Were major reforms needed? The obvious answer seemed like ‘yes.’ But that’s what progressivism is all about: making our systems of government work better for the people.

Then I started hearing calls to ‘defund the police’. This viral comic strip seemed to capture the gist of the idea:

Simplistically, it made sense. The programs that most help to prevent crime—social services that address homelessness, drug addiction, mental health, and so on—are frequently subject to funding cuts by cash-strapped local governments. But police funding was sacrosanct. Maybe a budgetary haircut for the police, who were always the largest line item in any local government’s budget, could help pay for these services, ultimately reducing crime, and motivate departments to stick to the necessities?

To be honest, a strengthening, visceral dislike of the police in general was also becoming a growing factor for me. While some neighbors posted “Black Lives Matter” yard signs like I did, others opted for “We Support the Police,” which just plain infuriated me. Couldn’t they tell how these signs would be received at this moment in history? As I became more and more sympathetic to the most extreme voices in the racial justice movement, even statements like “All Cops Are Bastards” seemed appropriate; it didn’t matter that the phrase had white supremacist roots— accounts like this one from an anonymous former cop suggested the sentiment was true. If I passed a black motorist pulled over by a cop, I seriously debated whether it was my moral obligation to u-turn, pull over, and record the exchange (I never did). I knew literally zero police officers in real life, but I felt confident believing they voluntarily joined an irredeemably racist and oppressive institution and therefore were irredeemable individuals for as long as they wore the uniform. In retrospect, the extent of my extremism, even if temporary, is embarrassing.

I’ve been on a journey of revisiting everything I thought I knew and looking at it all from “the other” perspective. Processing news stories and academic studies with an open mind to ideas that go against my intuition and a skeptical eye towards those that confirm my priors. Every step of the way, I see more and more areas where my previous perspective, which is widely shared by journalists, academics, and corporate America, seems to be doing far more harm than good to vulnerable populations. And when it comes to murder trends over the last decade, the signs look grim.

Anti-racists highlight examples of racial disparities as indirect evidence of systemic racism; no doubt, many of these disparities are deeply troubling, though their multivariate root causes are often difficult to decipher. One disparity that does not get as much attention as it should is the racial disparities in victims of murder. I did not know it until I was pulling together data for this piece, but black Americans are the victims of murder at 5 times the rate of Hispanic Americans and 9 times the rate of white Americans.1 Even more worryingly, black murder victim rates have risen approximately 40% since 2010. They comprise just over 50% of victims each year.

I’ll be blunt: for a privileged person like me to call for defunding or abolishing the police without remotely understanding the social dynamics driving this phenomenon is just reckless. If one genuinely cares about black lives, one must also care about reducing murder rates in America.

2020: A data deep-dive

After rising through the 1960’s and early 70’s, murder rates in the U.S. remained high for 20 years before beginning a 20 year decline whose root causes are still debated. In 1993 there were 9.51 murders per 100,000 people; in 2014, it was just 4.44. After rising slightly in 2015 and 2016, it looked like things might have been leveling off in ’17-’19. However the numbers for 2020 look lamentable: it’s likely we’ve surpassed 20,000 homicide deaths in one year for the first time in a generation.

Articles about 2020’s spike in murders often point to a Twitter post by criminological data analyst Jeff Asher. Official numbers through the FBI still haven’t been released for 2020, but in December, Asher manually collected numbers from major cities and homicide hot spots to find trends. He compared these statistics to past trends to roughly estimate that we should expect at least a 25% increase nationally over last year’s 16,425 homicides, putting 2020’s projected total at approximately 20,000 deaths or more. After downloading his data, I went down a rabbit hole of armchair data analytics. I updated some of his numbers with those from the Major Cities Chiefs Association where they were available. I also manually gathered a few more cities from the top 50 that he skipped. I used US Census data (2019 estimates) to gather population demographics for these cities. What follows is brief a summary of what I learned.

Murder is highly concentrated, with just 15 cities accounting for roughly 25% of homicides nationwide. The 66 cities I analyzed accounted for 17% of the US population but an estimated 43% of homicides.

Total numbers alone actually obscure just how concentrated murder is in the US. Once you normalize the homicide rates by population, you see several cities dramatically stand out. Six cities had murder rates of over 35 per 100,000 (the national average was about 6 per 100,000 last year; New York was actually below average at 5.24).

Comparing 2020 murder rates to 2019 murder rates shows that while eight cities’ rates stayed flat, most of the 66 cities studied saw a significant increase including seven cities whose murder rate nearly doubled. Linear regression (marked by the orange dashed line) shows an overall increase of about 30% for the cities analyzed. I broke the data set into three charts so that the city labels are decipherable.

What’s Going On?

In the various pieces published this year attempting to analyze this trend, several theories tend to dominate. I think German Lopez’s short list of top potential contributing factors is pretty fair-minded.

Pandemic-related shutdowns led to an increase in idleness and isolation in vulnerable groups, and suspension of many preventative programs

When people, especially teenage boys and young men, lack the right social connections and have a lot of free time on their hands, they’re more likely to get into trouble — spending time when they’d be at work or school on gang or other illicit activity, possibly to make ends meet or to socialize.

Protests over George Floyd’s death may have led to a breakdown in police-community relations.

Those breakdowns could impact violent crime in two ways. Maybe police, afraid of coming under criticism through the next viral video or acting in protest of the demonstrations, pulled back on proactive practices that suppress crime. Or maybe much of the public lost trust in the police, refusing to cooperate with them — making it harder for police to lock up offenders who go on to commit more crimes, and also possibly leading to more “street justice,” as more people distrust the legal system to stop wrongdoers and instead take matters into their own hands. Or a mix of both could have played a role.

A surge in new gun sales led to more guns in circulation overall, leading to more gun violence.

Lopez wraps by admitting it could be a mix of these, or none of these. The problem with this list is that it’s a veritable buffet of options to confirm your prior opinions about the world and show your allegiance to your tribe. Concerned about covid? It was the “economic and physical strain of the virus.” Hate guns? It’s (probably) the guns. Strong opinions about the police? It was Defund the Police! It’s definitely not Defund the Police!

Curiosity drove me down a data rabbit hole. Was there any data that could support or negate any of these theories?

Theory 1: The Pandemic

The National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice, organized by the Council on Criminal Justice (CCJ), put out a study examining trends for multiple categories of criminal activity over 2020 compared to prior years (I will return to it briefly). Outlets from NPR to Fox News covered the report, yet managed to frame it in strikingly different ways. The NPR story focuses almost exclusively on the pandemic theory: People are “cooped up,” “the criminal justice system is on pause,” “people are increasingly desperate … because of the concentration of poverty, tend to turn on each other.” Similarly, this NY Times piece states “Experts say the economic and physical strain of the virus, which disproportionately took lives and jobs from neighborhoods that were already struggling with high levels of gun violence, most likely drove the rise in shootings.” NPR and NYT are painting a picture to suggest that financially marginalized communities were pushed to the brink by the pandemic, driving up murder rates.

As a crude attempt to look at whether this might be a strong or weak factor in the rise in murder rates, I plotted the percent change in murder rate against the poverty rate for that city, per the U.S. Census. This assumes that there was no significant change in poverty rate between 2019, or that any changes in poverty didn’t vary much between cities, which is certainly a big assumption. But the data does not indicate that there’s much of correlation at all.

To be clear, murder rate does tend to be higher in cities with higher poverty rates; what this data says is that the 2020 increase in murder rates versus 2019 rates was not significantly higher in cities with high poverty. Now, this says absolutely nothing about the effects of the shutdown: lack of in-person school, employment, and community engagement activity all seem highly likely to have been part of the problem. But simple “despair” or “the economic strain of the virus” seems unlikely, especially since we thankfully did not see an increase in suicides, despite all reasonable concerns that we would. Also, the global nature of the pandemic gives us a natural experiment. Sadly, it appears that America was a global outlier in the rate of increase in murders we saw, despite having a more robust financial response than most of our peers; homicides stayed flat in both Mexico (with a much higher murder rate) and Canada (a much lower one).

Theory 3: Surge in gun sales

Setting aside Theory 2 for a moment, let’s address Theory 3. Here is the change in murder rates for the 66 analyzed cities, combined by state, compared to the annual FBI count of firearm background checks for 2020 versus 2019. (Note, the Y-axis reflects total murders in the cities on my list of 66 only.)

If anything, the data indicates that states where more guns were purchased might have had a smaller increase in murder rates than states with a smaller rise in gun sales.

Admittedly, I have never even touched a gun. They freak me out. If I could wave a magic wand, all guns would disappear along with the Second Amendment (sorry, not sorry). My intuition says if more guns are in circulation, then of course more people will die. However, we have to note that we only have data about legal gun sales, with background checks, which is the way the vast majority of new weapons move into circulation. We have no clue how many guns then move into the black market, never to be tracked again. Some studies estimate that in 80% of crimes that involve a gun, the gun was not legally owned by the perpetrator. When experts offer this theory, I’m sure they have reason to believe that when people purchase new guns legally, they resell old ones, which has a trickle-down effect eventually leading to more guns on the black market. And I suppose these guns could eventually cross state lines to commit crimes in other states. It all seems largely hypothetical, though; journalists have been pointing to the known surge in legal gun sales as the cause for concern, not the black market. It’s possible that the surge in legal gun sales could have lead to more killings outside of the cities I studied, but the data isn’t available yet to make a call either way. The jury is still out on this theory, but it doesn’t look likely. [Edited to add: Washington Post had a piece on June 14 which linked to a study claiming to show a correlation between gun sales and gun violence. I cannot yet determine why we’ve come to different results—I welcome reader insights.]

Theory 2: Anti-police protests

This theory has many layers to it, but they boil down to two: the police are doing something different, or citizens are doing something different, or both, in reaction to the police killings and the national response to them over the past few years. Last year’s protests were arguably more influential than any since the birth of Black Lives Matter; the most material impact was that dozens of cities did, in fact, move to reduce the budgets allocated toward their police departments. In reality, the cuts often ended up being dropped entirely or finalized as much smaller than initially floated. For the 42 cities whose budget changes were estimated by Bloomberg, the average cut was just 2.5%. I manually gathered data for the remaining cities with more than 40 murders in 2020 (if you need any sources, just let me know in the comments) and compared changes in murder rates to changes in police budgets.

Yet again, the correlation is extremely weak. This should not be entirely shocking. Budgets decided in mid-2020 would not take effect until 2021; additionally, several cities made headline-grabbing cuts (like Austin) that were predominantly reorganizations of which city departments oversee which services. I was somewhat surprised to see that in most cities, despite much public debate in June, final budgets protected or slightly increased police budgets after the fervor died down in late summer. Just as with the other theories, however, a scatterplot does not tell the whole story. Perhaps the seriousness with which a city’s City Council even debated defunding the police impacted police morale. Perhaps it reflects the latent mistrust of police in the neighborhood. 2020 was also a year of severe budget crises in many cities; if police budgets did get a trim, perhaps it was proportional to the rest of the budget?

Regardless, I've still come to regret my previous support for efforts to defund the police. I certainly still support a dramatic increase in funding for social services as a way to invest in the people in underserved communities. But as I’ve learned more about policing, and the people who’ve been working for decades to make policing more effective and community-oriented, I see now how they too can be part of the solution, if properly funded.

Ghettoside: A brief synopsis

On the recommendation of fellow Substacker Graham Factor, I recently read the fascinating Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America, by Jill Leovy. Leovy, a former homicide reporter with the Los Angeles Times, embeds herself for over a year with a homicide detective team within LAPD’s South Bureau. Deaths in communities like the Seventy-seventh Street Division she describes in the book account for a large portion of, but far from all, homicides in the U.S.. Throughout the book, Leovy depicts every person she encounters with compassion and humanity.

Let me say up-front that the book was a bit jarring at first. She unflinchingly describes a community in pain from “black-on-black crime,” a phrase I’d long considered to be blatantly racist. (In Ijeoma Oluo’s So You Want To Talk About Race, she states bluntly, “Yes, black men are more likely to commit a violent offense than white men. No, this is not “black-on-black” or “brown-on-brown” crime. Those terms are 100 percent racist. It’s crime.”) However, Leovy is attempting to describe a specific dynamic within specific communities; far from an indictment of black people or black culture, she describes with compassion the historic and systemic root causes, and the resulting psychological carnage, of gang-related violence in certain low-income urban communities (which, it’s important to note, are only a subset of predominantly black communities nationwide). Here are a few of my major takeaways from the book:

Police departments are comprised of many different teams, each with their own sub-culture and objectives; she often emphasized the differences between homicide detectives (whom she was embedded with) and patrol officers, aka street cops or beat cops.

Community members have a complex relationship with police officers. Some distrust police due to negative personal interactions. Some disdain the police for lack of action, lack of protection, or lack of resolution to previous crimes. Most hold skeptical at best or hateful at worst views of the police. Leovy depicts several mothers of homicide victims who have reason to assume that the white or Hispanic detective assigned to their son’s case won’t care about “just another black man down,” but eventually a few of the detectives are able to earn their trust through dedication to solving the case.

Homicide detectives are each different; many grow cynical and judgmental, but the best ones stay obsessed with solving murders. The primary focus of the book is on the death of Bryant Tennelle, son of detective Wally Tennelle, an LAPD officer who proudly insisted on keeping his family in South Central. Prior to his son’s death, Wally Tennelle’s motto for each murder victim was that they were “some daddy’s baby.” Lt. Skaggs, the primary detective on Bryant’s case, adopts the motto as his own. It did not matter what kind of a life the victim led; their family deserved justice.

There is a cyclical nature to homicide in these communities. Young men, eager for a sense of belonging and importance (as all young people are), join gangs with strong alliances. Shootings are sometimes initiation rites, but are more often an escalation of an argument, or even retaliatory for the shooting of a friend. Mistrust in the criminal justice system can lead to vigilante justice.

Street cops are the face of the police department in communities. Their deployment can sometimes cause more harm than good, as when Leovy describes the all-out response to a shooting of a child that wastes resources and angers the community. But they can also provide critical evidence to help solve homicides. Tennelle’s case is cracked open when the murder weapon is discovered during a routine drug deal bust.

Budgets have a big impact on the way departments are run. It influences whether cops can work overtime (for good or for bad), whether the detectives are properly resourced to keep up with the caseloads, whether officers are getting adequate time off, training, or mental health services, or even whether witnesses can be protected and/or relocated for their safety.

Murders in these communities can be extremely hard to solve, and yet a common refrain of residents is that “everybody knows” who committed any particular crime. Residents have compelling reasons to stay quiet. The justice system is slow to act and inconsistent. If they agree to be witnesses, they put themselves and their families in danger from the killer’s associates for years without certainty that the killer will serve time. On top of that, guns are rarely registered and change hands frequently; people go by a half-dozen nicknames that make leads hard to follow.

That being said, solve rates can vary wildly by detective. Some detectives clear only 30%, others over 80%. Many cases are officially closed as “cleared other,” which means no conviction was secured, but the police have reason to believe the primary suspect is either in prison for another crime or was killed themselves.

For every homicide, there are dozens of “almocides” (“almost a homicide”). These are shootings that avoid fatalities only by pure luck. Almocides can leave the target physically unscathed but psychologically driven to retaliate, or they can permanently injure or maim the victim. These are not always reported to the police, so the true prevalence of gun violence can be difficult to accurately understand.

I’ll leave it to the reader to learn more for themselves by checking out the book. It’s compelling, eye-opening, heartfelt, and upsetting.

The distrust/violence feedback loop

With some important exceptions, this graphic loosely matches the book’s description of how interactions between residents and police can cause a feedback loop leading to a growing surge of homicides.

The Trace is an anti-gun violence advocacy group, so they include “proliferation of gun carrying” in the cycle, which I don’t have knowledge to support or deny. And I’ve discussed before how it seems likely that fear (reasonable or not) plays a factor in how officers interact with civilians; fear (or precaution, or reasonable reaction, depending on your perspective) would increase as local violent crime rates go up, since the odds also go up that the person you’re interacting with has committed a violent crime.

The biggest flaw in this mental model, however, is that it treats local communities as a self-contained system not influenced by the outside world. The “bubble” that’s missing on this chart is the general public, as amplified by the national media and social media. National attention amplifies incidents of police misconduct that fits a certain mold, dialing up police mistrust nationwide. Public pressure to reform police departments or constrain their budgets leaves police under-resourced to solve crimes or proactively prevent them. National reaction to police misconduct leads to some officers being overly cautious or wanting to avoid paperwork, skipping proactive stops entirely. (Please be sure to check out Graham Factor’s expert take on the phenomenon of “de-policing.”) Many cops in over-worked departments say “fuck this” and retire early or move to lower-stress departments, but the cost to backfill them is too high, and remaining cops are left even more overloaded. There are so many ways these factors start to interact, it quickly turns into a rat’s nest.

There has been much debate over the past 6 years about the so-called “Ferguson Effect,” a term first popularized by conservative firebrand Heather Mac Donald. She controversially claimed that violent crime had started climbing nationally in mid-2014 after the protests in response to Michael Brown’s killing due to public pressure on police officers to reduce proactive policing and avoid becoming the next headline. I believe the systemic interactions are complex enough that it’s easy to strawman your opponent’s argument, as this otherwise thoughtful Slate article did (“[T]he notion that protestors opposing police brutality are somehow responsible for rising crime rates is ludicrous.”). In 2015, trends were still mixed; some cities saw huge increases in murder (including Baltimore in the aftermath of Freddie Gray’s death) while others went down. But in the years since, and especially in 2020, criminologists now do feel like the national upward trend in killings that began in 2014 is real.

So what happened in 2020?

I want to return to the CCJ report I mentioned earlier. I found it interesting and worrisome that the NPR story cited the author of the report as saying “there may be factors beyond pandemic-related economic and mental health issues at play” but never did explain those likely factors. This is not because the CCJ report itself avoids the issue. It studies different categories of crime across 34 cities and four years to look for statistical “breaks” in the data—points where the data significantly deviates from annual trends. Crimes that decreased in 2020, like burglary or drug offenses, show a break at the beginning of the pandemic. However, the authors identify a different finding for homicides:

Per the authors:

Homicide rates were higher during every month of 2020 relative to rates from the previous year. That said, rates increased significantly in June, well after the pandemic began, coinciding with the death of George Floyd and the mass protests that followed. Overall, homicide rates increased 30% in 2020 [in the cities studied], a large and troubling increase that has no modern precedent. An increase of this size in large cities suggests that the national homicide rate increase almost certainly will exceed the 10.2% increase in 2016, after police killings in Ferguson, MO and elsewhere sparked widespread protests, as well as previous largest single-year increase of 12.7% in 1968.

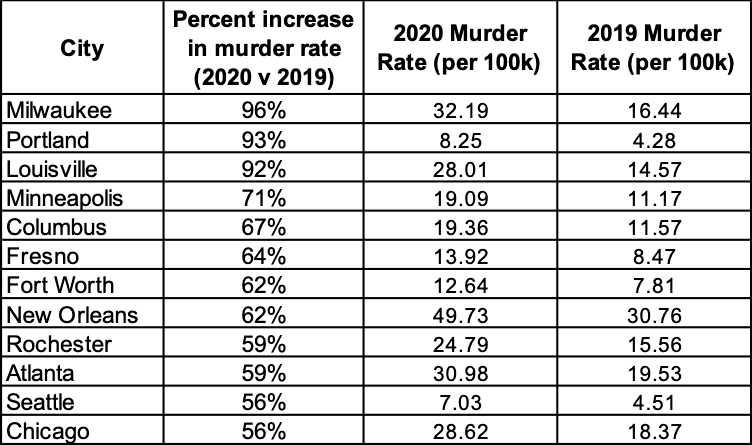

In a final return to the 2020 data, here is a list of the 12 cities with the largest increase in murder rate out of cities with more than 50 killings last year:

Notice a pattern? Jacob Blake, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Daniel Prude, Rayshard Brooks. Portland, New Orleans, Seattle. It’s hard to look at this list and not see a strong correlation with last year’s headlines and subsequent epicenters of protests. The pandemic may have added tinder, but it seems like the headline-grabbing police killings and resulting unrest lit the match.

What next?

The Council on Criminal Justice does not leave us wringing our hands, however. The report urges cities to act now to reduce violence using tested methods (most of which would require an increase, not a reduction, of policing budgets). Recommendation 6 of 15 from the CCJ Task Force urges us to “Target High-Violence Cities with Evidence-Based Strategies”:

America’s high rate of urban gun violence is perceived to be one of the most intractable issues of our time, but 30 years of rigorous social science demonstrates that certain strategies can save lives. When implemented with fidelity, a short list of evidence-based interventions such as focused deterrence and cognitive behavioral therapy have reduced shootings and killings in dozens of cities.

A new federal grant program supporting such strategies could demonstrate that urban violence is simultaneously one of the most serious and solvable social challenges facing the nation today. This proposed program would direct significant operational federal dollars to the localities most in need, building on current efforts at the U.S. Department of Justice that offer training and technical assistance. Funding would be explicitly tied to the data-driven, evidence-informed strategies that are proven to reduce violence, a balanced mix of enforcement and non-enforcement approaches.

In the fight to provide social support for communities in need, it does not need to be a zero-sum game. Community leaders and criminal justice professionals can partner together to implement programs that continue to build on decades of progress, if we can just stop pitting them against each other.

These conversations make a lot of upper-class progressives uncomfortable, including ones who work for NPR or the New York Times. We feel the weight of responsibility to make society better for those with less influence, and yet we are far too ignorant of the day-to-day realities of the lives of either police officers or citizens in impoverished communities to have any clue what effective solutions would look like. We are often so focused on the internal cleansing to rid ourselves and each other of racial biases that we go to extremes to avoid possibly reinforcing any negative stereotypes. Before we know it, we start to subconsciously internalize a “poor black people have no power” framework, which in turn leads to us to shrug our shoulders and accept high murder rates in marginalized communities as an inevitable consequence of our nation’s white supremacy. At that point, how could the police possibly do anything but make things worse?

Last summer, I knew I did not have the experience of living in these communities and could not personally speak to root causes of violence. I deferred to activists who suggested that they spoke on behalf of entire communities when they advocated for defunding or abolishing the police. However, I never stopped to acknowledge that I also did not have any lived experience in studying or fighting crime. I took too long to learn that these activists’ demands do not always reflect the beliefs of many in the most affected communities, who often just want better policing. Ultimately, these issues are complicated and I just have no business ignorantly advocating for radical systemic changes that could backfire in violence and death. There are people who’ve dedicated their lives to researching these issues; many of them are academics, many are community members and activists, and many of them are police officers. Community members absolutely have power, influence, and an active role in shaping social programs and public safety policy to fit their needs. The best ideas to address complex problems come from diverse groups of people working together toward a common goal… and saving lives is a goal we should all be able to agree on. Until we learn to work together, we will continue to see a tragically increasing number of young people die.

Historical murder and non-negligent homicide data is from the FBI UCR. Racial breakdown of victims was estimated based on a reported subset available in the FBI UCR Expanded Homicide Data for each year. Murder rates were calculated using annual US Census estimates of populations by racial category. Hispanic breakdown of murder victims into white and black races was estimated using US Census data as well. All calculations performed by me and charts created by me, so tell me if I screwed something up.

Marie, This is stellar work. I am crying, as the mom of a cop, and an historical liberal, who has learned so much in the past year.

A train of thought . . . .

1) Excellent post, thank you. I am aware of my own ignorance on many of these topics and appreciate the research (and agree with your conclusions, "Community leaders and criminal justice professionals can partner together to implement programs that continue to build on decades of progress, if we can just stop pitting them against each other.")

2) FWIW, I consider myself fairly far out on the "liberal" end of American politics but I was never inclined to advocate for de-funding the police. I did speak at one of the local public forums on, "race and policing" to advocate for a Civilian Review Board -- which is unlikely to be a major change but seemed like a good idea.

I do appreciate that I never felt like that position put me in conflict with people that I think of as ideological allies. There is a group of local activists who were inclined towards the, "all cops are bastards" position, but I wasn't in the same circles as them, and I didn't feel any pressure to sign on to that viewpoint.

3) I am, by nature, an incrementalist. I think the right solution to most social problems is to figure out ways to chip away at the problem, make small improvements, and build on them. But the moment, last summer, when I was most sympathetic to the viewpoint of, "incremental change isn't enough; there needs to be a major reckoning with the degree of harm that the is being caused under the status quo" was watching Amber Ruffin (who is charming and just about the least threatening person in the world) talking about her experience with the police: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8o6OEyfuJU8

4) I remember a very simple point from Mark Kleiman's book on criminology _When Brute Force Fails_ that reducing crime as an (extremely large) social good, prisons, and courts are a cost. Much of our political discourse talks about imprisoning people ("getting dangerous criminals off the street") as a benefit in itself. But Kleiman emphasizes that the benefit is the reduction in crime and that punishment is expensive and we should think about how to most efficiently direct carceral resources to get a reduction in crime at lower cost (both financial and human costs).

The same is true of police -- I think that the police do an extremely valuable job, but having police (and particularly armed police officers) is a cost. Without wanting to insult the many people doing the job well, I think it's reasonable to have a conversation about, "how can we best reduce crime while minimizing the ancillary costs?" (and, again, I'm personally much more concerned about reducing the human costs imposed by policing than the financial costs, but I don't begrudge somebody looking at the $10B budget for the NYPD, for example, and wanting to have some reassurance that the money is being spent well).