More lives have been ended far too early; more families have been shattered. Daunte Wright, a 20-year-old man from Minnesota, was shot and killed by a police officer, leaving a 2-year-old son to grow up without his father, and his parents Katie and Aubrey to mourn as they bury their own son. Adam Toledo, just a 13-year-old child, was shot and killed by a police officer in Chicago. His mother Elizabeth described her seventh grader as “full of life.” Maryland 16-year-old Peyton Ham was shot and killed by a state trooper in his own driveway. His family has shared they are “heartbroken and shattered.”

These deaths hit me especially hard this week. You don’t have to be a mother yourself to understand what a gaping hole it must leave in your heart to lose a child in such a manner. The suddenness, the senselessness. But more than that, the violation of public trust. These were officers who were sworn to “protect and serve.” This is the service we are supposed to be able to call if we were to ever fear deeply for the life of our child. And yet, they were responsible for ending their lives instead? The path from pain, to fear, to anger, to hatred seems to be repaved again and again with every hashtag.

Police fear civilians

It is completely understandable to me why some call to abolish the institution of policing all together. With its dark history and tragic outcomes like these, maybe we are better off starting all over again? I hope we can agree that we all deserve to live in safe communities, free from fear of our neighbor or from the police themselves. Where we have well-funded community-wide services that promote the health and well-being of everyone, young people especially. Inevitably, we will need an entity dedicated to ensuring that laws against violence and theft are enforced and that justice is able to be served for the victims of crimes; it is absolutely critical that those who are sworn to “protect and serve” are properly trained and equipped to do so for all citizens, as representatives of the citizens themselves.

Many argue that it is better to reform and improve policing from where it is today than to rip it up and start all over. Given that this sentiment is shared by a majority of the country, including a large majority of black and Latino voters, it does seem worth considering. Robert Shrewsberry, former police officer and founder of the Institute for Criminal Justice Training Reform, was interviewed on NPR this weekend about what he thinks we should do to minimize these tragedies in the future. It’s a brief interview and worth listening to in full, but he lays out up front the major concerns he has with the way officers are trained for duty today (emphasis mine).

ELLIOTT: You were an officer for 13 years, and you attended three different police academies in the early part of your career. Did you feel that the training you received was not adequate?

SHREWSBERRY: No, and there's a couple of issues that I saw with training. No. 1 was just, was there simply enough time. And this is using today's data. So when we look at just criminal law, on average, police officers only receive about 60 hours of training in law. And that has to cover constitutional law, federal criminal law, federal transportation law, state criminal law, state traffic laws, local ordinances and civil liability. There's just no way in the period of time that they're given that they would be able to be trained adequately.

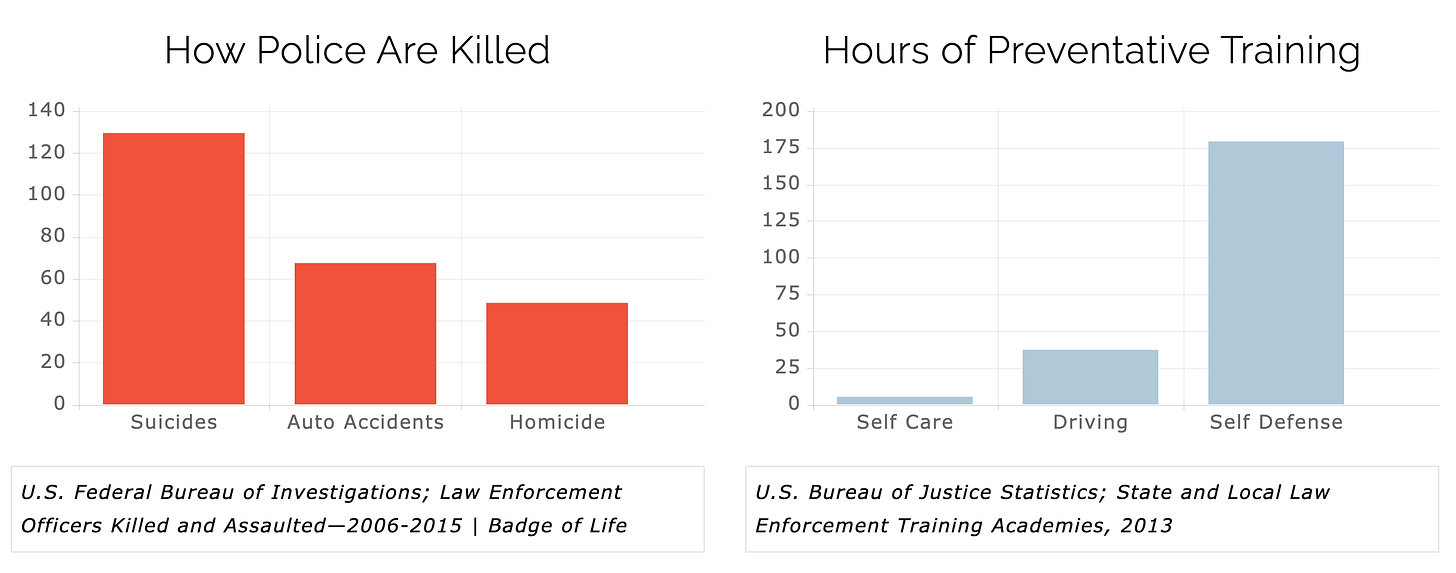

Now, the other issue that I saw is fear-based models of training. What this leads to is a training of possibility versus probability. And so officers are reacting to things that probably are statistically unlikely to happen. Or if they were to happen, it was very anecdotal. If it's a warrior-based style training, then that implies the rest of us are potential enemy combatants. But it's stressful for the officers themselves. And what we know is, is police officers are far more likely to kill themselves, nearly five times as likely, than to ever be killed in the line of duty. And we think that this kind of fear-based training is contributing to that.

Most everything I know about the training or job experiences of modern police comes from movies, television, or liberal-leaning news outlets like NPR or Vox. That is to say, I do not know much. I know exactly zero police officers in real life. That being said, Shrewsberry’s logic resonates with me; it does not make a lot of sense to me why a group of people with so much power would receive so little training. As an engineer who designs machines that could kill people, I went through 6 years of formal higher education and over 1000 hours of formal on-the-job training. And while there was certainly a level of fear instilled in us over the seriousness of our responsibility to ensure product safety, we ourselves had no reason to fear for our personal safety while on the job. Mastering the technical and mental skills to balance the need to protect your own safety and the safety of others is a monumental task that would surely require lifelong learning and practice.

In an attempt to better understand the realities of modern policing, I’ve been subscribing to The Graham Factor. Last week he shared this horrifying video.

Officer Darian Jarrott, father of two, was shot at point blank range during what he thought was a routine traffic stop. It’s a graphic reminder that, even if these incidents are rare, they do happen; approximately 50 officers are killed each year in the line of duty. Officers need to be able to decide in less than a fraction of a second if the civilian they’ve just encountered is a kid with an airsoft gun or a drug lord with an AR-15. How can you ensure that every single officer is equipped to make that decision correctly 100% of the time?

Shrewsberry’s organization’s website provides some interesting insights.

These charts, if correct, paint a worrisome picture. Officers are inundated with videos like the one above of Officer Jarrott being slaughtered in broad daylight, or these officers being shot in Tulsa. They are taught to fear for their lives in every encounter. As Shrewsberry says, they are too often taught possibility, not probability. Fast forward to timestamp 40:25 in the video below to hear a former officer describe what he was taught in the academy.

Tatum’s description is jarring, but believable. Police officers undoubtably cross paths with violent criminals far more often than the rest of us; it’s literally their job. In the interest of keeping them safe, officers are inundated with self-defense training to wire their brains to be on high alert at all times. This has the positive effect that officer deaths in the line of duty is quite low. But it has several terrible side effects—one of which could be the fact that suicide is a 250% higher risk to an officer (note, Shrewsberry’s claim of 5x that he made in the interview does not match his own data). Upon reflection, this is not shocking, given officers’ easy access to firearms and extremely high stress levels. The organization Blue HELP reports that suicides among first responders dropped back down to 171 in 2020, roughly equal to 2018 levels, after surging to 238 in 2019. (It is important to note, however, their suicide rate is lower than the population at large.) And yet given the risk, officers appear to receive only an average of 6 hours of mental health self-care training, 1/30th of the time spent preparing to defend themselves against external threats. With nearly 700,000 police officers in the US, the odds that they will actually be shot and killed in an interaction over the course of a year is less than 0.01%.

The birth of a bias

Biases are created and perpetuated when people receive lopsided information that exaggerates one aspect of reality and neglects mitigating information. Biased people make biased decisions that hurt themselves and others. Biases turn reasonable fears into irrational anxieties. A new parent is justified in learning about the risks of SIDS, but can become obsessed with their child’s safety to the point that they deprive themselves of sleep, or worse, engage in unsafe methods of bedsharing. Someone distrustful of the COVID vaccine may latch on to stories of extremely rare complications as justification for skipping the vaccine themselves, and may worry about friends and family who did get them; their avoidance of the vaccine ultimately puts themselves and their neighbors at a much higher risk of COVID itself. Someone shaken by the terrorist attacks of 9/11 might spend the next few decades tuned in to news sources that amplify the risk posed by terrorist extremists, and this fear and anxiety could cause them to more easily subscribe to racist or xenophobic thoughts about Muslims or immigrants. Unchecked, fear breeds crippling anxiety or hate-filled resentment, to the detriment of everyone.

So how do we fight fear? It’s an age-old question. A willingness to learn and accept accurate information about the probability of a risk is a good place to start. In the case of police officers, a more accurate depiction of the level of risk posed during encounters versus driving or risk of suicide should be both explicitly addressed and implicitly reinforced through balancing time spent on the different messages. The reasonable fear of making a mistake and hurting a child or innocent civilian should be a factor in training (if it isn’t already). Reflecting on potential race-based biases that hamper an officer’s ability to accurately assess risk seems reasonable, but unfortunately does not seem to be effective. I suspect this is due to ironic process theory; reflecting on a negative association, even in an attempt to suppress it, will only strengthen it—replacing it with a positive association is far more effective. Finding more ways to break down the cultural barriers that separate cops from the civilians and communities they protect and serve would have to be a net positive. In a speech at Cornell College on Oct. 15, 1962, Martin Luther King Jr. said, “… I am convinced that men hate each other because they fear each other. They fear each other because they don’t know each other, and they don’t know each other because they don’t communicate with each other, and they don’t communicate with each other because they are separated from each other.” How can we find ways to connect, communicate, come to know each other, overcome fear and prevent hatred?

Civilians fear police

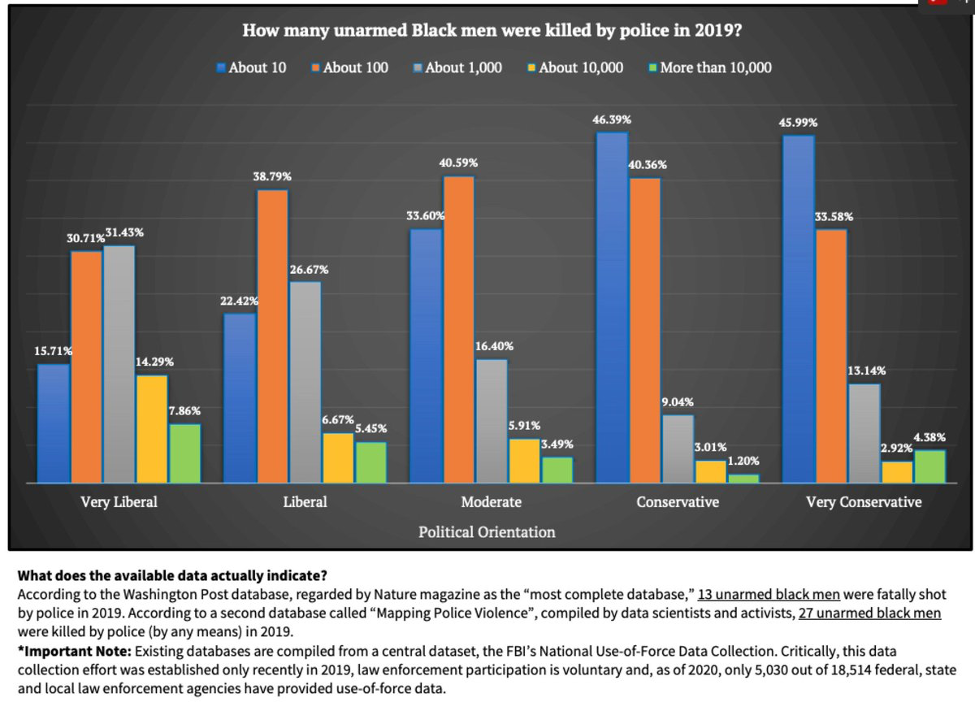

The truth is, police officers are not the only ones who are receiving a lopsided accounting of reality, feeding fear and anxiety to the detriment of all. The media environment of the average liberal-leaning American amplifies the threat of death at the hands of police officers, especially for people of color. A recent survey asked people to estimate how many unarmed black men were killed by police officers in 2019 (h/t again to Graham Factor).

The median “very liberal” respondent estimated about 1,000; the median “liberal” or “moderate” went with about 100. “Conservative” and “very conservative” respondents were most likely to answer about 10. The correct answer, depending on whom exactly is counted, is around 27. To be clear, this number is 27 human lives too high for me! Beyond that number are many more people killed who were white, Latino, or other races, or who in some way “armed;” many more who were maimed or otherwise brutalized but survived, and thousands who were simply harassed or abused. Police methods should continue to change until all deaths, assaults, and abuse at the hands of police, of armed or unarmed civilians, is as close to zero as humanly possible; we must hold sworn officers to the highest levels of responsibility. And yet, this survey clearly conveys that the public has an extremely biased perception of reality today, and an extremely exaggerated understanding of the risk of death to unarmed black men. Note also that “liberal” or “very liberal” respondents estimated that 56-60% of people killed by police were black; the real number is around 23%.

Even knowing the real numbers, it can be extremely hard to assess what they mean in isolation. How much fear should a young black man, or the family of a young black man, carry that he might face death at the hands of a police officer? We know it’s a possibility, but what is the probability? Studies like this one boldly conclude that death by cop is a “leading” cause of death for young black men; sixth leading, by their accounting. But where is the bar chart comparing this mode of death to the top 5, which include accidents, suicide, murder, heart disease, and cancer? The data is nowhere to be found. The LA Times, to their credit, pulled CDC numbers and added the study’s result, finding it 7th on the list for black men 25-29. I took the liberty of making a graph myself. I used the Washington Post database to break up the 3.4 per 100,000 police use of force deaths into armed (where I only included cases labeled gun, knife, or other weapon) and unarmed (where I included vehicle, toy gun, and unknown cases along with unarmed.

A 28 year old black man who does not carry a weapon is 77 times more likely to die in an accident, 26 times more likely to commit suicide, and 3 times more likely to die of the flu than he is to be killed by a police officer. (I am setting aside for now the heartbreaking and unfathomable risk of death by assault or homicide faced by young black men who live in some deeply impoverished neighborhoods, which is reflected in the first bar.)

If we want to make sure police officers know that their risk of suicide or car accident far outweighs their risk of being killed by a civilian, so that they can manage their fears and interact safely with others, we should want the general public to have the same accurate understanding of their own risks during police interactions, for their own health and well-being.

The gap between perception and reality is understandable; it reflects the media we consume. If we get most of our news through our Twitter or Facebook feed, we will see the stories that go viral—these are the stories that match our biases and feed our fears. When I did a Google search for their names, Daunte Wright, a black man, yielded 23 million hits. Adam Toledo, a Latino boy, yielded 6 million. Peyton Ham, a white boy, yielded 29,000; Officer Jarrott, 165,000. This is not a matter of what’s “fair;” people will read, comment, and share the stories that match their interests. But it is important for us to “mind the gap” between perception and reality, especially when the bias is exacerbating long-standing fears and anxieties.

The pain of fear

The headlines I see from New York Times and Washington Post this weekend alone are overflowing with personal stories of fear, anxiety, grief, and trauma among black Americans. It’s clear why:

“We’re constantly turning on the TV, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and seeing people that look like us who are getting murdered with no repercussions,” said Pittman, an organizer for A New Deal for Youth. “It’s not normal to see someone get murdered by the click of a video on your phone, yet it has become the norm for our people, our Black and brown communities.” [Source]

This is not a distant hypothetical to me. It has been the deep, sincere, and terrifying pain felt by my closest friends and co-workers who fear for their own lives, and the lives of their sons, husbands, and brothers, that has been my north star for any anti-racist choices I’ve ever made. All I’ve ever wanted in this arena is to help fight for a world where they can breathe a sigh of relief, and live lives no more crippled by fear than any of the rest of us. And yet it has become clear to me now that the national conversation is making this fear worse, not better. It’s moving us backwards, not forward.

Jonathan Capehart’s piece, Being Black in America is Exhausting, hit me hard. He describes his life as living “under siege.” He illustrates the multitude of small, but cumulatively overwhelming, steps he takes each day to minimize his own risk and the appearance of threat he poses to others. It is sobering to read, as a white woman who has never felt the urge to worry about these things. He proffers that “The one comfort I take in this harrowing time is that fewer White people will write off what I listed above as petty or paranoid.” He describes the relief he felt upon receiving a message from a white friend stating that Capehart “wake(s) up every morning to a world that doesn’t appreciate you.” I genuinely feel for Capehart, and I do understand the roots of his pain. But at a certain point, can’t we see that we are exacerbating the pain of our loved ones by reinforcing an inaccurate perception of the world? This is Jonathan Capehart we’re talking about! Yes, he is black, and he is gay, and neither of those attributes make life easier. Despite the challenges he has surely faced, he won a Pulitzer Prize, he’s on the editorial board and a regular columnist for the Washington Post, he has his own weekly 2-hour show on MSNBC, he’s regularly featured on PBS NewsHour and many other prestigious television shows. I appreciate him. Huge swaths of America appreciate him. I do not think he is being petty, but I can’t help but think he is suffering a painfully high amount of mental anguish given the objectively higher-than-average amount of appreciation the world has for him. Would the world appreciate him even more if he were white and straight? Possibly. And to be clear, fame and prestige does not mean he will always be treated with respect by police; just ask Henry Louis Gates Jr. But as a not-poor, middle aged black man, the fact is that his risk of a fatal encounter is a vanishingly tiny fraction of even the average twenty-something unarmed black man depicted above. His risk of suicide or health complications from stress-induced high blood pressure is likely thousands of times higher. At what point does the fear itself become more dangerous than the thing being feared? How do you let someone you love know they seem to be suffering from crippling thought distortions without making them feel like you are judging them as paranoid, or worse, gaslighting them? Without falsely suggesting that you don’t care about police brutality? If you cannot reassure Jonathan Capehart, how can you reassure your struggling friend or co-worker? I genuinely do not know.

I hope we can just start with a more accurate depiction of reality in our media sources. Articles like this one in NYT that describe police killings as “mounting” in the shadow of the Floyd trial distort reality, not depict it. “Since testimony began on March 29, at least 64 people have died at the hands of law enforcement nationwide, with Black and Latino people representing more than half of the dead.” However, no link to raw data is provided and nothing clarifies whether this is a deviation from past trends or not. “Three deaths a day” is stated with no context that this is, in fact, the running average for the last five years (and 2021 is actually tracking low so far). There is no breakdown of armed versus unarmed victims; in Washington Post’s database, an average of 87% of deaths listed involved a weapon. Specific examples of victims are highlighted, all of them black or Latino, despite nearly half of the victims in this timeframe being white or another race. Several activists are quoted to link these incidents to the agony experienced by so many people of color across the nation. One spokesperson for the Fraternal Order of Police attempts to provide an additional perspective, sharing how hopelessness and lack of trust in both directions between civilians and officers leads to an increase in crime and in hostile encounters. “‘There’s just so many factors that people have already made up their minds and they think that law enforcement is based off of race,’ said Mr. Yoes, who is white,” the piece quotes. I do not know what purpose the addendum “who is white” is meant to serve other than to trigger the reader to think that this man is biased and untrustworthy.

The bias associating the three concepts of whiteness, policing, and danger comes through in more than just news media and social media. The acclaimed fictional series, Lovecraft Country, features a family of black Americans struggling to survive in 1955 Chicago (spoilers ahead). The series is beautifully done and thrilling. It is a genre-bending, unconventional mix of sci-fi and historical fiction. The main characters are multi-layered and surprising. And yet, literally every single white character that is encountered (and there are many) turns out to be entirely evil and devoid of humanity. Several, the police officers in particular, are literal demons. The only white character who momentarily seems like she might have an ounce of heart, Christina, turns out to be the worst one of all, betraying those foolish enough to trust her and murdering the main character, Tic. The series ends with Diana, Tic’s niece who overcame demonic possession at the hands of white police officers/dark magicians, using her mechanical arm to crush Christina’s neck until she dies a righteous and satisfying death. It was a visual enactment of that terrifying nightmare where you have to choke someone to death with your bear hands just to save your own life.

As a white person who watched the show, I did not feel fear that it would exacerbate anti-white racism that I would somehow fall victim to. I watched it in despair that such a message could be so carelessly broadcast to a nation in the middle of a traumatizing mental health crisis.

An Epidemic of Fear, an Antidote of Love

Upon encountering the Martin Luther King quote above, I went in search of other thoughts he had to share on fear. Unsurprisingly, he had much to say. In his 1963 sermon “Antidotes for Fear,” captured in his book, Strength to Love, he give a powerful analysis of the nature of fear, and begins to chart a path forward. It’s worth quoting at length (though I apologize for excerpting portions—please visit the link to read it in its entirety).

Sigmund Freud spoke of a person who was quite properly afraid of snakes in the heart of an African jungle and of another person who neurotically feared that snakes were under the carpet in his city apartment. Psychologists say that normal children are born with only two fears—the fear of falling and the fear of loud noises—and that all others are environmentally acquired. Most of these acquired fears are snakes under the carpet.

When we speak of getting rid of fear, we are referring to this chronic abnormal, neurotic fear. Normal fear protects us; abnormal fear paralyzes us. Normal fear motivates us to improve our individual and collective welfare; abnormal fear constantly poisons and distorts our inner lives. Our problem is not to be rid of fear but rather to harness and master it.

How, then, is it to be mastered?

First, we must face our fears without flinching. We must honestly ask ourselves why we are afraid. The confrontation will, to some measure, grant us power. We can never cure fear by the method of escapism. Nor can it be cured by repression. The more we attempt to ignore and repress our fears, the more we multiply our inner conflicts and cause the mind to deteriorate into a slum district.

[…]

So let us take our fears one by one and look at them fairly and squarely. By bringing them to the forefront of consciousness, we may find them to be more imaginary than real. Some of them will turn out to be snakes under the carpet. Let us remember that more often than not, fear involves the misuse of the imagination. By getting our fears in the open we may end up laughing at some of them, and this is good. As one psychiatrist has said “ridicule is the master cure for fear and anxiety!”

[…]

Now what does all of this have to do with the fears so prevalent in the modern world such as the fear of war, the fear of economic displacement, the fears accompanying racial injustice, and the fears associated with personal anxiety? It has so much to do with them that we can find an illustration at almost any point. Hate is rooted in fear and the only cure for fear-hate is love. Take our deteriorating international situation. It is shot through with the poison darts of fear—Russia fears America and America fears Russia; China fears India and India fears China, the Arabs fear the Israelis and the Israelis fear the Arabs. The fears are numerous and varied—fear of another nation’s attack, fear of another nation’s scientific and technological supremacy, fear of another nation’s economic power, fear of lost status and power. Fear is one of the major causes of war. We usually think that war comes from hate, but a close scrutiny of responses will reveal a different sequence of events--first fear, then hate, then war, then deeper hatred. If a nightmarish nuclear war engulfs our world—God forbid—it will not be because Russia and America first hated each other, but because they first feared each other.

[…]

Hatred and bitterness can never cure the disease of fear, only love can do that. Hatred paralyzes life, love releases it. Hatred confuses life, love harmonizes it. Hatred darkens life, love lights it. Hatred has chronic eye trouble—it cannot see very far; love has sound eyes—it can see beneath the surface and beyond the outer masks.

We are facing a national epidemic of fear. People of color live in mortal fear of those sworn to protect them. Police officers live in mortal fear of death in the line of duty. The rest of us choose sides and live in a much pettier fear of challenging the perceptions of people we love. Are we all willing to “use eyes of love” to help look for the snakes we think are under the carpet?

This is admittedly easy for me to say, a white woman with a white family, with a desk job where my biggest on-the-job risk is carpal tunnel. But I offer it up in love, and I hope that collective love and clarity will help us identify real solutions to save lives and protect mental health. Let’s improve officer training to ensure the probability of risk is properly calibrated, and officer mental health is given more priority. Let’s rebuild trust with over-policed communities by prosecuting misconduct by officers and securing convictions, removing unfit officers from duty forever, investing in the detective forces that bring justice to families ravaged by violence, and investing in the residents of these communities themselves. Let’s reframe the national discussion so that we are not afraid to paint a clear picture of reality, resisting the temptation to sensationalize some tragic deaths and ignore others, resisting the urge to dehumanize people based on their profession or their worst mistake. Let’s challenge our own assumptions and stereotypes by taking time to learn about people who live very different lives than us. Let’s challenge media narratives that perpetuate fears based on those stereotypes, to the detriment of the mental health of already marginalized groups.

The antidote to bias is reality. The antidote to fear is courage. The antidote to hate is love.

Great piece! Took me an extra day to get to it; I was dropping my wife off for a silent retreat in a neighboring state. It was interesting to see how other folks "do" the fight against Covid-19.

Two thoughts on your article. First, it seems to me that many of the issues concerned with the police reflect their strongly held positive self-image. If the cops and their friends could just recognize why others have a different idea, we could make progress toward a rational discussion.

Second random idea, could we have some sort of federal training for cops, perhaps after a year or two on the job. Once the cops have the training -- let's say a month of training -- they'd get some sort of certificate that makes them eligible for a benefit of some sort. The training would cover the sorts of issues that make more sense once you've actually been on the job. Obviously this requires more work, but the basic idea is to find some positive ways to encourage progress rather than simply to yell at the cops for their failings.

There’s a lot of info to process here (and kudos for pulling together the data that was missing). My first impression is that when we talk about emotions like fear, courage, hate and love; these exist on spectrums and there’s a lot of gradations in between fear and courage or hate and love. Most people probably can’t move directly from one extreme to the other, and will need to travel through a few stages to get there. Some might get stuck at indifference. I think it may be worthwhile to examine what are pathways between these. If step one is gaining perspective (removing the bias that obscures reality), then is step two turning down the temperature of rhetoric?

My own intuition says that people must accept that we live in a complex and non-binary reality, and that what seems obvious may be an illusion so we cannot be so confident in our own rightness. Then we must be curious. You, in particular, have demonstrated this exceptionally well.