Writing near the edge

Sentimentality is the flaccid safety tether I can’t detach from. Not yet.

I spent a little time with James Baldwin this week. I’m an engineer, not an English major; prior to last year, my only knowledge of Baldwin was from meme-ified quotes ready-made for social media but stripped of all context and humanity. On the advice of Chloé Valdary, I recently decided to dig into his 1949 essay, Everybody’s Protest Novel. Honestly, it somewhat makes me want to just shut this whole enterprise down because what value could my drivel add to mankind’s understanding of itself compared to that? (Seriously, go read it. This can wait.) There are so many ideas in that essay alone worth savoring and rolling around in your head for weeks at a time. But there is one passage that punched me in the stomach in a particular kind of way.

“Sentimentality, the ostentatious parading of excessive and spurious emotion, is the mark of dishonesty, the inability to feel; the wet eyes of the sentimentalist betray his aversion to experience, his fear of life, his arid heart; and it is always, therefore, the signal of secret and violent inhumanity, the mask of cruelty.”

This passage comes early in the essay as he is critiquing the prototypical protest novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for its moral superficiality. About the main character, Yankee Miss Ophelia, shouting down her slave-owning cousin, “This is perfectly horrible! You ought to feel ashamed of yourselves!,” Baldwin observes, “Miss Ophelia’s exclamation, like Mrs. Stowe’s novel, achieves a bright, almost lurid significance, like the light from a fire which consumes a witch.” … Holy shit, read that again. At just 24, Baldwin needs just one sentence to masterfully contrast the violent extremes that some people are willing to go to enforce their self-assured moral doctrine on others with the shallowness of their own understanding of their shared human nature. “…what constriction or failure of perception forced her to … leave unanswered and unnoticed the only important question: what it was, after all, that moved her people to such deeds.” Baldwin further explores achingly deep themes of the human struggle (which deserve their own, separate post to discuss), but at the end of his essay, he turns his sights on the “modern” protest novel, Native Son, by his friend and mentor Richard Wright. Wright, like Stowe, resorts to caricatures that do not challenge shallow, classification-based stereotypes but reinforce them. “Below the surface of this novel there lies, it seems to me, a continuation, a compliment of that monstrous legend it was written to destroy.”

Apparently and unsurprisingly, Wright was deeply hurt by Baldwin’s critique. At the start of his career, Baldwin had sought out Wright as a friend and mentor after reading Native Son and viscerally relating to the world of Bigger Thomas, that of impoverished black life in the tenement buildings of New York City. He even titled his 1955 collection of essays Notes of a Native Son as a nod of respect towards Wright’s influence, with “Everybody’s Protest Novel” included as the first essay. Later, Baldwin explained, “I knew Richard and I loved him. ... I was not attacking him; I was trying to clarify something for myself.”

Baldwin’s philosophy on writing is right there in the essay. He rejects sentimentality as a lie, a farce, a cheap way of avoiding hard truths; a way of avoiding full acceptance of one’s humanity; one more bar in the “cage” that “betrayed us all.” Once one feels they’ve glimpsed the rawness of human nature that “that move[s] … people to such deeds,” if one is fortunate enough to ever suspect they might have, to Baldwin, it’s nothing short of intellectual dishonesty to sweeten it up, dial it down, sand off the edges. Moral integrity compels you to lay it all out there, even if you condemn yourself in the process. Even if you might damage a treasured friendship.

I am not that brave.

Engineers are trained not just to solve problems but to assess and mitigate risk. Every creation has the potential to both benefit mankind and to kill a man. Weak engineers are paralyzed by overestimated risk, weighing down their ideas with so many factors of safety that they ultimately do no harm to anyone because the ideas never reach a state of existence. Reckless engineers are instead obsessed by their own ideas, or lulled into a false sense of complacency, and lose sight of the buildup of risk until risk bites back with injury or death. The best engineers are constantly measuring risk accumulation against risk appetite, burning it down through controlled experiments until the team determines that the creation clearly presents far more benefit to humanity than danger.

When it comes to dangerous ideas, I’m certainly more direct here, under the cloak of anonymity and a “borrowed intellectual property” avatar, than I am at work or on social media (which I’ve effectively abandoned). I try to use this space as a controlled experiment, to measure benefit against danger. But I still hold back. For one thing, it’s pretty freaking self-aggrandizing to even humor the idea that you might have some observations to share about human nature that most people don’t already see. To then consider that sharing those precarious observations boldly, with no sugar added, with no mixer or chaser, would not just alienate much of your potential audience, but damage your very real friendships, or even put your job at risk? Why take the chance?

So I cling to sentimentality like a security blanket. And yet, it hasn’t protected me.

Through the fall and winter, I attempted to share some of my changing views and questions with some close college friends. It was a weird experience for me—it was only through challenging and then changing my beliefs that I realized how inextricably melded my beliefs and my “self” had become. It was as if I was going under the knife to have a tumor removed, except the doctors weren’t 100% sure it wasn’t actually a vital organ they were slicing out. I was desperate for the people I loved and cared about most to hear me out and say, “Oh man, yeah! I get it, you’re so right!” I’m sure from their perspective, my desperation turned into something resembling harassment. I kept trying to lay out my case via text message, no sentimentality or overly emotional dialogue involved because I thought 20 years of friendship would have rendered that unnecessary. One friend finally flat-out told me she needed a break, that “people like” me were “part of the problem.” I was hurt, but I understood, and I figured that giving her space was our best hope of eventually reconciling. I decided it was unhealthy for me to be channeling so much of my energy into trying to change my friends’ minds to reassure my own, and a blog would be a healthier outlet.

When I started Post-Woke, I did not share it with my friend who’d put me on probation, but with a few other mutual friends. In the moment, it felt intellectually dishonest to hide it from them. As you can see from my first two posts, and really all of them, I can be heavy on the sentimentality. Baldwin’s rebuke has sent me soul-searching: is my heart arid? Am I cruel and violently inhumane? Unable to feel?? My earnest goal was and always has been to assure my reader, whomever they might be, that I care about them, and in that way, my sentimentality is rooted in an overly abundant ability to feel. I care about how you, the hypothetical reader, feel and how my words affect you. I want to share my thoughts, but somehow not hurt or offend anyone. And in that way, Baldwin’s accusation is fair: my sentimentality is undeniably rooted in fear, and arguably dishonest, as it leads me to hold back and over-edit.

Yet, what did these contortions achieve? I estranged yet another formerly close friend, one who had generously been there for me after I’d angered the first. In her defense, I casually sprung the invitation to read this blog via text message, and I regret ever sharing it, honestly. I don’t think she knew what it would be about until she started reading, and it probably took her off guard. I thought a blog form, where I could explain ideas at length, add sugar, soften edges, would help my friends better understand my concerns and observations than text messages. But a blog, like an essay, is not a conversation; it’s a broadcast. There’s no room for your conversation parter to interrupt with “let me stop you there…” to share an (often needed) alternative perspective. The reader is effectively strapped to the chair and told to listen until I’m done. I’m not exactly sure what I wrote that crossed the line for my friend; she didn’t tell me except to say she was deeply offended and she did not care to speak to me about these topics ever again. She reassuringly shared that she didn’t think I was a bad person, but she wasn’t sure what kind of “ideology” I’d gotten myself into. She cited some examples of systemic racism that she lives with day in and day out in such a way as to suggest that she thought I somehow no longer believed it existed, which just left me confused and ashamed. Deep shame washed over me for weeks. Maybe I was “into” something dark if I was now an unacceptably small number of degrees of separation away from people who cruelly assume impoverished black people don’t work hard?

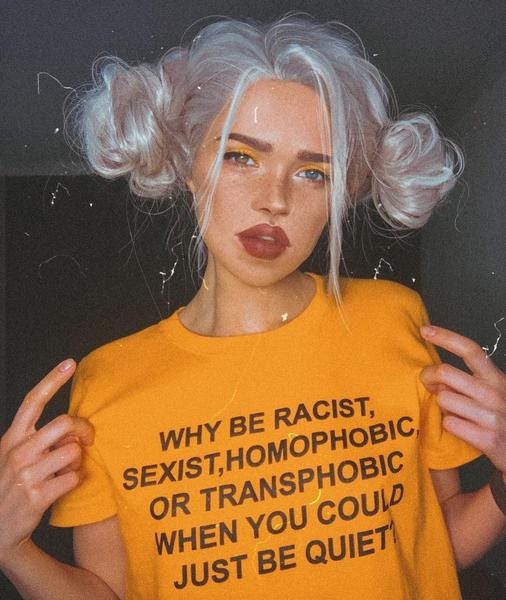

Growing up (and I’m calling ages 18-37 “growing up”) within a worldview that still doesn’t have a widely accepted name, but we’ll call it wokeness, really fucks with your brain. This t-shirt’s message is a wonderful example of how simple the world can seem: “Why be racist when you could just be quiet?” Why, indeed?!

In this world, racism (and sexism, homophobia, and transphobia) of any form or amplitude is the ultimate evil; worse than cruelty or intellectual dishonesty or alienation or indifference. The choice to engage in a line of thought that the shirt-wearer considers to be racist is never acceptable (note that this is a subconscious or conscious attempt on the part of the shirt-wearer to garner power, as they become self-declared judge of what qualifies as racist). The speaker must be shamed into silence, for the greater good. “This is perfectly horrible! You ought to feel ashamed of yourselves!” To be clear, this was a righteous claim on judgement that I long harbored myself. The threshold for what I considered to be racist was so obvious, people who violated had to be malicious or reckless (or, when I was feeling generous, ignorant). The label “racist” came to be so broad and so shallow as to encompass any perspective on race that I deemed “problematic,” and in a similarly shallow way, disqualify a wide range of views that I had no problem with from being similarly labeled. Like Stowe, I’d never properly reflected on “what it was, after all, that moved … people to such deeds.” Only when new ideas that rhymed with ideas I’d reflexively burned at the stake for decades wanted to come earnestly out of my mouth did I fully understand how difficult it is to be both intellectually honest and avoid offending people you love.

I did, however, learn that there is a time and a place for such conversations. I visited my closest college friend for the weekend a couple of months ago. I’ve never shared this blog with her, but she was one of my few college friends who was willing to talk to me over the phone for a few hours about this subject. Flying cross-country to spend 48 uninterrupted hours with her, I was terrified. Could we avoid these topics entirely? Should we? What would happen if she decided only hours into my visit that I was irredeemable and needed to leave her home immediately? I decided to err on the side of shutting the heck up; our friendship was too important to me and I no longer felt desperate for external validation. In the end, my fears were immensely overblown. We had a fantastic weekend reconnecting and discussing topics both personal and universal. I leaned into listening instead of lecturing, sharing my perspective only when it seemed relevant and appropriate. I could see her face, and 20 years of familiarity made it easy for me to instantly read when my thoughts weren’t landing the way I intended them to. Her thoughts shaped mine and mine hers. And we could just relax, drink wine, and laugh about stupid shit too. After a year of Covid and, for both of us, identity-altering shifts in life circumstances and perspectives, it was invigorating to tap into the lifeblood of a friendship that formed a far more fundamental piece of our identities, one that wasn’t predicated on passing a particular ideological litmus test. None of this can be remotely replicated through the written word.

You, reader, cannot tell, but I often struggle to decide what to write about in a given week, though it’s not for lack of ideas—quite the opposite. I have a running list of dozens of ideas, from deconstructing the constituent pieces of systemic racism, to exploring what it would even mean to be racist about white people, to comparing the toxic effects on society of the ideas of both Charles Murray and Robin DiAngelo. These ideas consume the oxygen in my mind all week long, sometimes at the expense of being productive at work or fully enjoying quality time with my family. But for every idea, there are two challenges. The first is how to tame the messy, nebulous, hairball of an “idea” into a linear succession of words, messenger RNA to transfer to the reader so that they can recreate some semblance of the original idea in their own mind. The second is to try to anticipate how the reader’s ideological immune system will react to such an idea entering the body. This ideological immune system can begin attacking an incoming idea before it has even fully re-formed, attempting to both amplify its threat and pummel it into submission. What sticks can end up being a deformed, ugly mutant idea that serves to strengthen the recipient’s immune system against future, similar ideas. My assumption had been that adding sugar will help the medicine go down—no threat here! I mean you no harm!—but that assumes I am offering medicine worth taking at all, or that the sugar won’t destroy its impact. On the strength of his convictions, Baldwin would just go for the chemotherapy.

And yet, there’s a fine line between chemotherapy and poison. Dosage, diagnosis, and a practitioner’s expertise can mean the difference between a new lease on life, and death itself. I’m definitely no Baldwin; maybe these ideas, in my amateur hands, really are dangerous? My prior worldview certainly provided me ample tinder to throw on the bonfire to incinerate these threats at the stake. Terms like “white savior,” “sealioning,” “concern troll,” “toxic positivity,” “gaslighting,” and of course “privileged” still regularly pop into my head, shaming me for even daring to entertain problematic ideas, much less release them upon the unsuspecting world, regardless of (or perhaps, in response to!) how much I sweeten them. The inoculative effects of these concepts have proven long-lasting, even when the (perceived) threat is coming from inside my own mind.

It’s not clear to me whether Baldwin and Wright ever truly repaired their relationship. With a critique that raw and personal and undeniably true, it’s hard to imagine their mentor-mentee relationship could have ever been the same. But Baldwin did not enter the pantheon of great American literary minds by playing it safe. Did he always hit the mark? Honestly, I don’t believe he did. Being human and all, he was as susceptible to being trapped by his own illusions as any of us. But his contemporaries who played it safer have been forgotten over the years. By being unafraid to be bold, in his risk-taking, he gave us all the reward of timeless insights about humanity.

This is an excellent essay, Marie.

Acolytes often wind up stabbing their mentors through the heart, so Baldwin's response to Wright is nothing new. It's how writers and intellectuals grow and separate themselves. (Most of the famous cases are of men; are there well-known cases of women doing so? Memo to self: Research this.) And Baldwin was a difficult guy with difficult relationships. I don't think it's bad to add some sugar to the medicine.

What do you want from your friendships? To be seen and heard and understood, and still loved? Some friendships will survive that test. Others, ones that are more rooted in shared tribal beliefs (to put it in current jargon) won't. You know Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Sonnet 14? The first part reads:

If thou must love me, let it be for nought

Except for love's sake only. Do not say,

"I love her for her smile—her look—her way

Of speaking gently,—for a trick of thought

That falls in well with mine, and certes brought

A sense of pleasant ease on such a day"—

For these things in themselves, Belovèd, may

Be changed, or change for thee—and love, so wrought,

May be unwrought so.

We have friends who love us for a trick of thought that falls in well with theirs and brought a sense of pleasant ease. But Browning is right, those things can and do change. It's painful, but it's part of the human condition. I hope I don't sound dismissive; when I say it's painful, I mean it's *really* painful. From my own life experience, though, I can tell you that my best friends have come to see that everything is a lot more complicated than we thought it was when we were young and starry-eyed. Those friendships endure.

I hope you keep writing and finding your voice. You may need to experiment with adding or subtracting sugar to find your own authentic speech.

Oh, and visiting friends in the flesh is invaluable. Face to face allows for more melding and communion. It just does.

This is very well-written and thoughtful, Marie. The pain that many of us feel over our alienation from our former tribes is devastating. I feel fortunate, in some ways, that I moved for retirement right before Covid so am not physically close to many of my woke friends. I keep my mouth shut, mostly, on social media. Two years ago, I was giving trainings on "White Fragility"; now I'm just begging for some understanding of nuance. And, not to be creepy, but if you ever want to fly out to the Pacific Northwest, we have a guest room and access to wine!