What do we tell the children?

Dueling moral panics over teaching kids about racism overlook one fact: the adults never even agreed on what racism is.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve come across a story (or ten) about critical race theory in K-12 schools over the past few months. Unless you’ve been working in academia or have an advanced degree in law or humanities, you’d probably never even heard of CRT prior to 12 months ago. How can something go from near obscurity to fiercely contested in such a short span? How can an esoteric legal theory (that even PhDs accuse each other of not accurately understanding) be remotely relevant to K-12 education? Many writers have shared their interpretation of CRT, its various bastardized forms, and why either the advocates or attackers (or both) are somewhere between ignorant and maniacal. Jeet Heer is right that the anti-CRT movement is a form of moral panic, yet he misses that from their perspective, the anti-racist movement they oppose is also a form of moral panic. At the heart of this doom loop of competing moral philosophies is a simple problem: while nearly all of us agree racism is vile, we have totally different conceptions of what it is and why it’s wrong. Is it any wonder that we can’t agree on what to teach the children?

Reading, writing, right and wrong

There was a manager at my company who always seemed to have a “business cliche of the month” in his back pocket. For a while, it was that we needed to make things “Sesame Street simple” for some presentation. The co-opting of the name of my favorite childhood institution in the service of corporate buzzword lingo did not sit well with me, but like most business platitudes, there was a nugget of wisdom there. Framing a strategic message in such a simple way that even a child could understand it ensures all members of the team, no matter how large or diverse, have clear direction. With everyone operating from a common, simple, well-defined set of flexible running rules, a team can accomplish great feats.

From a human, evolutionary standpoint, it’s hardly shocking that most parents have very strong opinions when it comes to teaching their kids right from wrong. I’ve argued before that the moral binaries of right and wrong are like the 1s and 0s of a society’s operating system, the “Sesame Street simple” rules we agree on within a community that help us trust each other, collaborate and thrive. It makes sense that evolution would work in favor of individuals who feel innately compelled to form groups through shared morality, and that groups that prioritize passing along that morality to their offspring would be more likely to flourish. To most parents, teaching our kids right from wrong feels almost as important as keeping them physically safe.

Sharing schools with other parents only works when we all roughly agree on a range of content we want our children to learn together. We agree we want them to learn to read, write, do math, and understand history and the basics of science (with some notable, relevant exceptions). When it comes to morals and ethics, most of us want our kids to be honest, respectful, industrious and cooperative. Work hard, be nice. We like to think the lessons our kids learn in childhood set the tone for the rest of their lives, or that they’ll come back to them as adults. In the 1980s, Robert Fulgham wrote the zeitgeist-defining best seller “All I Really Need To Know I Learned in Kindergarten” which included such advice as share everything, don’t hit people, don’t take things that aren’t yours, and take a nap every afternoon. I can still remember the posters that adorned many a classroom wall, both promising wisdom and mocking me for bothering to show up for third grade.

Childhood lessons are simple and powerful programming for how we live the rest of our lives. Having grown up with Mr. Rogers and Sesame Street, I enjoy watching them again with my preschool-aged son, and can sometimes feel a swell of emotion when a particularly poignant message hits me like a blast from the past. It’s amazing how overwhelmingly complex the moral conundrums of the world can seem when compared to the simplicity of the most resonant, time-tested lessons we choose to pass along to our children. And yet the most foundational moral lessons—kindness, resilience, generosity, humility—come back to us time and time again in moments that matter.

We’re different, we’re the same

Since at least the 1960s (or, arguably, 1619), the fight against racism has been our nation’s biggest moral quandary. It’s obvious to the point of cliche that Martin Luther King Jr. dramatically altered the course of American history through his contributions to the civil rights movement, perhaps most of all with his 1963 speech at the March on Washington. He not only brought into stark relief the extent to which we were not living up to our own founding ideals as a nation, he offered a corrective: judge someone not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. Sesame Street simple. Note he did not prescribe strict color blindness; during his life, he supported efforts to enact Affirmative Action legislation through the Great Society. But when it came to individual treatment of one another, our interpersonal social contract, he urged us to remember that race was inconsequential compared to moral character.

His vision became the bedrock of two generations of anti-racism. Early advocates like Mr. Rogers shocked some members of his audience in 1969 by welcoming a black man, Officer Clemmons, to join him in sharing a wading pool on a hot afternoon.

It’s a mistake to minimize the effect that a gesture like this, a display that would not even be noteworthy today, had on audiences at the time. According to François Clemmons, who played Officer Clemmons, that scene changed the course of many lives.

“And many people, as I've traveled around the country, share with me what that particular moment meant to them, because [Mr. Rogers] was telling them, 'You cannot be a racist.' And one guy or more than that, but one particularly I'll never forget, said to me, ‘When that program came on, we were actually discussing the fact that black people were inferior. And Mister Rogers cut right through it,’ he said. And he said essentially that scene ended that argument.”

This same basic moral lesson—we’re all equals, regardless of race—was passed along by the Baby Boomers to their Gen X and Millennial kids. Most of my peers were raised on Sesame Street classics like this one from 1981: despite our differences, we all sing the same song, and we sing in harmony. (You’re welcome in advance for the earworm.)

I was a bit old for Sesame Street by the time “Whoopi’s Skin and Elmo’s Fur” came into rotation in 1990, but with two younger sisters and a soft spot for the Muppets, I saw it enough times to remember it vividly. As the largest and most visible human organ (as well as being highly distinguishable between groups of people), of course kids will see and be curious about skin, so it makes sense to discuss it with them. Sesame Street never shied away from seeing skin color, noting it as one of many things that makes each person unique, and encouraging kids to not wish to “trade” with anyone else. (Elmo asking to touch Whoopi’s hair would probably not fly today.)

Watching these videos stirs up warm, communal emotions for most people in my generation and my parents’ generation. They are kid-sized depictions of King’s vision of the Beloved Community, where “racism and all forms of discrimination, bigotry and prejudice will be replaced by an all-inclusive spirit of sisterhood and brotherhood.” Is it any wonder that so many Americans in the mid-to-late 20th century chose to, if not give up their prejudices entirely, at least shield their children from the toxic world views they grew up with?

And sure enough, across all sorts of measures, anti-black attitudes among whites decreased steadily through the late 20th century and early 21st century, paving the way for the election of America’s first black president. It’s not a Beloved Community yet, to be sure. Explicit and subtle discriminatory attitudes absolutely still exist and lead to bias, vitriol and violence in communities around the world. There is still a lot of work to do, but that does not mean King’s moral clarity was wrong.

King himself predicted, “It is this type of spirit and this type of love that can transform opponents into friends. It is this type of understanding goodwill that will transform the deep gloom of the old age into the exuberant gladness of the new age. It is this love which will bring about miracles in the hearts of men.” King was making a vitally important point: holding bigoted views about others hurts not just others, it hurts you too because it prevents you from entering into a brotherhood of goodwill with them. Millions of Americans were promised as kids that if we could all stop caring about each other’s race and learn to appreciate each other for who we are, we could live in harmony. Is it any wonder they’re pissed when people say that believing that fairy tale makes them the racist?

Colorblindness is the new racism

Look—I absolutely recognize how trite and naive that all sounds. Love alone won’t fix mass incarceration, or underfunded schools, or intergenerational poverty, or prohibitively expensive health care, or unconscious bias in hiring, or any of the other systemic barriers that lead to far too many people in America living at a quality of life far below what most of the rest of us take for granted. The bundle of problems that get grouped together under the umbrella of “systemic racism” are complex and interconnected; a messy confluence of interpersonal biases, institutional favoritism, intergenerational advantages, and intercultural distrust that absolutely impacts some racial groups more negatively than others. Critical race theory was an attempt to explain why it seemed like the liberal ideals of the 1960s civil rights movement had failed to deliver continued advances into the ’70s and beyond. Racism was not merely the sum total of individual racist attitudes; it was now a system of advantage that collectively benefits white people more than all other racial groups. CRT (correctly) claims that racially neutral policies can still create or perpetuate unequal racial outcomes. In a strictly academic sense, CRT is defendable: it’s a legal school of thought with a diverse set of practitioners who often disagree with each other, so while it frequently has outlandish claims associated with it, there’s always someone else who challenges those claims from within. It existed for nearly 50 years without being noticed even by professors on the other end of campus. Why the controversy now?

Most of us know by now that “CRT” is a label that’s been (sometimes callously) applied to a wide swath of topics remotely related to the topic of racism. I won’t defend the people who are using it as a battle axe (or sword) in the culture war, or resorting to clumsy, overreaching, authoritarian restrictions on free speech. But it’s a mistake to assume the backlash is predominantly due to white conservatives wishing to perpetuate their own racial advantage. Exclusively looking at the issue of racism through the lens of CRT leads one to adopt a moral code that runs directly orthogonal to Kingian anti-racism—dramatically different standards of behavior depending on the race of the actor and the person they’re interacting with. Through a Kingian lens, CRT’s fixation on “whiteness” itself as the foundation of racism promotes racial stereotypes and distrust of white people, which ends up hurting the people who hold these views most of all (admittedly, a claim worthy of its own post). The messages and ideologies being protested violate every lesson against racism they’ve heard their entire lives—namely to treat everyone as equals, regardless of their race.

I admire Rod Graham because, even though he is firmly entrenched on the progressive side of the Great Woke War, he often sincerely engages on Twitter with people who he disagrees with. More than once, I’ve seen him make what I think is an insightful observation, but he still manages to come away with the opposite conclusion than I would. Here he accurately observes that a major part of the resistance to modern anti-racism is that generations of children were indeed taught something fundamentally different about the nature of racism than what is being promoted today. Revisiting the moral lessons of our childhood, it’s no wonder that so many adults today sincerely believe that the very act of assigning importance to someone’s race is racism. The moral sin of racism for these people lies not just in the relative position of one race over the other in some sort of social pecking order, but more fundamentally in preferring, generalizing, or stereotyping human beings on the basis of race at all. Graham views this belief as inherently bad, a form of indoctrination that needs to be undone for others as he was able to undo for himself.

“Critical race theory” has become a crude catch-all label for the policies and perspectives that start from the premise that there is a racial hierarchy in America (and the world) that puts white people at the top, that most people and policies uphold it unconsciously, and—crucially—that colorblindness is immoral because it “blinds” one to the racism we “swim in,” depriving one of the tools or motivation to “dismantle” it. It’s an understanding of racism whose very definition is racist from the colorblind perspective because it requires the discrete categorization of people by race. As a framework for personal behavior, it’s inherently asymmetrical, with dramatically weaker moral boundaries on thoughts or actions toward whites as a group or as individuals so long as they’re in the service of dismantling white supremacy. Graham is right that people are recoiling, but he fails to see how it’s often a sincere reaction to seeing a new form of the racism that many were “indoctrinated” for decades to oppose. If someone genuinely believes that all races are equally worthy of dignity and respect, why wouldn’t they be upset by stereotypes or bigotry aimed at people of any race, regardless of the race of the person professing those views?

The complex issues raised by critical race theory are ones of moral philosophy, historical myth-making, and governmental design. These are issues that adults with good intentions disagree on in good faith. There’s nothing “Sesame Street simple” about them. And yet, many are concerned that as a moral perspective, it has begun to permeate children’s programming and could turn back the clock on decades of racial progress.

Time to wake up the kids

Released in 2014 at the dawn of the Great Awokening, “Beautiful Skin” is not the banger that “We All Sing The Same Song” is, I’m sad to say, but its message is of the same spirit. Children of all races play together and acknowledge their skin colors, this time explicitly—umber, cinnamon, ebony, ivory. It might have made the extreme colorblind-advocates uncomfortable if they felt it was unnecessarily drawing attention to skin color, but I doubt it would elicit protests in the street. All colors were acknowledged and celebrated as equals.

Flash forward to 2021. “Color of Me” is also not one I’m likely to get stuck in my head. But it’s a noticeable shift from “Beautiful Skin”: only shades of brown are acknowledged. I did not find it offensive myself, but would this not just reinforce the flawed message that fairer skin colors are not notable because “white” is the “default”?

“Color of Me” was part of a surge of Sesame Street programing on the topic of race in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. The web-only feature “Explaining What is Race?” came out in March of this year and it features Elmo learning from his new friend Wes that “our skin color is an important part of who we are.” You can imagine how well that went over in some corners of the internet. Granted, the rest of the video makes it clear that despite our differences, we can and should come together and “stand strong.”

The most vitriol was directed toward a series of PSAs from Cartoon Network, which were aimed at slightly older kids and were far more explicit. The characters practically sneer at the concept perpetuated by “Sing the Same Song”—it certainly does matter what color your skin is, and claiming to be colorblind is effectively just a tactic to avoid discussing racism.

For someone on the conservative end of the spectrum, this departure from Kingian anti-racism is both confusing and enraging. Many on the right assume modern anti-racist advocates are just “grifters” who know what they’re doing: purposely stirring up division in order to sell books and drum up votes for Democrats. Having sincerely lived on the advocacy end of the spectrum, I disagree with this take. Most anti-racist advocates are sincere as can be. They see a world of stubborn racial disparities perpetuating for generations. They feel that these disparities are largely due to attitudes among white people: comfort in a system they benefit from; subtle biases in favor of other white people that are learned during childhood, reinforced in adulthood, and guarded by false claims of colorblindness. Comparing people from black and Hispanic communities who tend to build a significant portion of their identity around their race with white people who generally prefer to downplay their race, they see the white norms as nefarious denial in defense of privilege. This explains the urge to reach the children: in a society where we’re all “swimming in racism,” children will pick up on their race, the race of others, and their relative ranking; they must be taught early to see race and recognize the races as equals, while resisting calls to be colorblind, which were too often used as a bludgeon against black people and their allies attempting to highlight instances of racism.

I’ll admit, even at my peak wokeness, there was something about all this that didn’t quite feel right to me. I still felt that members of all races were equal, that races were a social construct, and that everyone should be treated with respect. Systemic white supremacy was vile and needed to be demolished. But I struggled to determine what, exactly, I was supposed to be teaching my (white) two-year-old son to help him be part of the solution. Teaching him that he was white and that that was “an important part of who he is” felt like the wrong direction. The concepts were too complex, and any “Sesame Street simple” takeaway resulted in awkward inconsistencies. I eagerly purchased a copy of Antiracist Baby by Ibram X. Kendi, hoping he’d cracked the code on how to translate this gargantuan problem into kid-sized ideas.

He hadn’t.

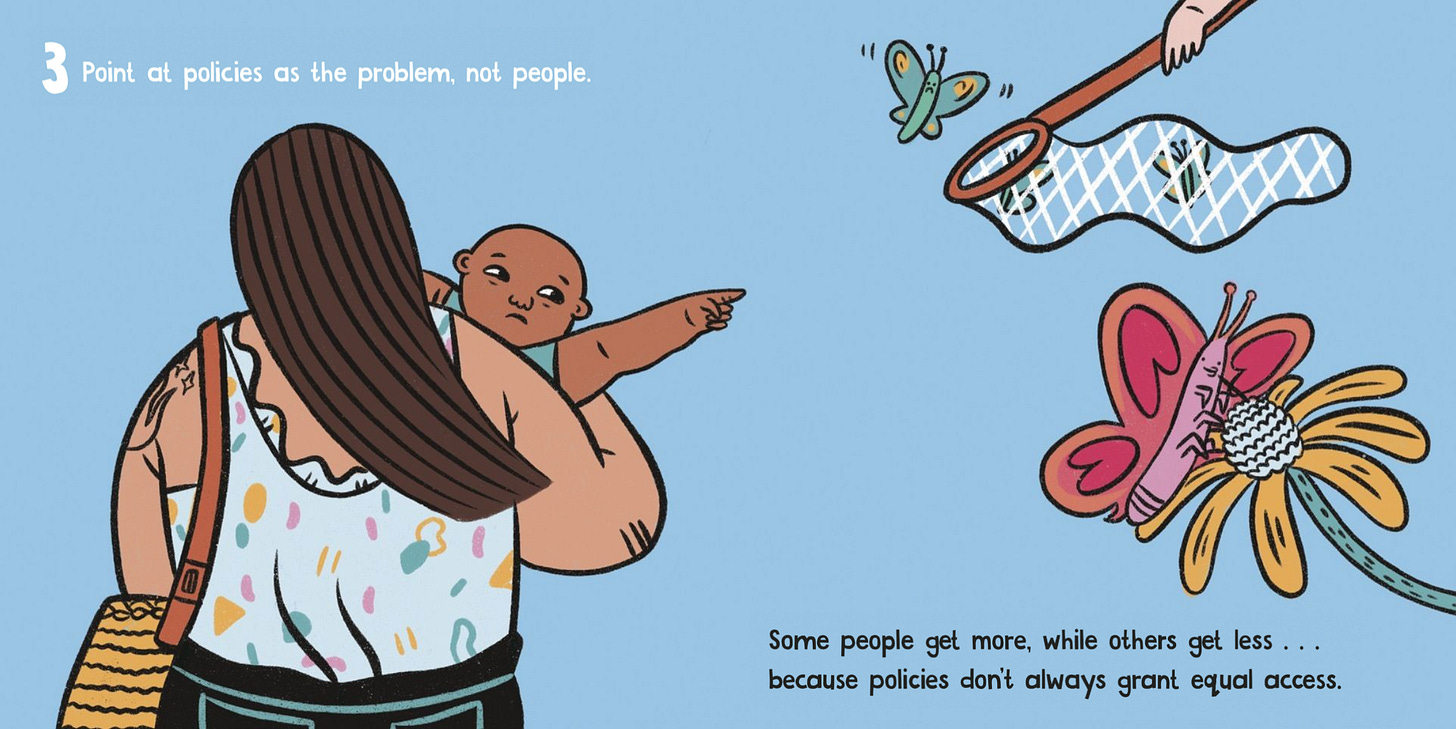

Contrary to the 4,700 five-star reviews, I’m calling this book’s bluff. He never defines racism (as he generally struggles to do). He uses words like “policies,” “confess,” and “disrupt” (though thankfully not “disparities”) that are outside the understanding of most grade schoolers. But worst of all, it just doesn’t make sense unless you’ve read his book for adults. I actually think many of his ideas are not as bad as many people claim, and he doesn’t get enough credit for challenging several common tenets of pop-CRT like “black people have no power” and “it’s impossible to be racist against white people.” But it’s clear that his entire philosophy is centered on defending race-based affirmative action policies, eliminating standardized testing, and ending mass incarceration. Which, ok, mature adults can debate and discuss—there shouldn’t be a need for kids to read board books to prepare them. But there is, because despite his claims to the contrary, Kendi has contorted the entire framework of racism to moralize positions on race-based policies such that to support them is to be antiracist (good), to oppose them is racist (bad). The moral weight of policy positions is genuinely felt by Kendi and his followers… and children need to learn morals early.

What should we tell the children?

The most frustrating part of this whole debacle is that we don’t actually have to agree on the existence or workings of systemic racism or the best policies to promote equality in order to reach a decent agreement on what to teach young children (of all races, backgrounds, and socio-economic statuses) in school to prepare them to fight racism.

Try to treat everyone with kindness, understanding, and generosity—even the people who seem mean or angry. Sometimes they just need a hug.

Work hard, don’t give up easily, and help make your community better for everyone. You don’t always get what you want, but you have more control over your own destiny than anyone else does.

You will have some things easier than other people, and some things tougher. Be grateful for what you have and find ways to support those with less. Practice compassion.

Look out for the people who are being left out or ganged up on. Reach out to them and be kind. Set an example for others.

Sometimes rules can seem unfair. If you see a way things could be done better, speak up and offer to help make it happen. Find compromises.

Some people will say or do things you don’t like or don’t agree with. Stand up for what you feel is right, but stay kind and treat others as you want to be treated. Listen and keep an open mind.

American history is a mix of great and terrible. Look back on history to learn both the best and the worst of what humans are capable of. Be inspired by the best; learn lessons from the worst—regardless of their race or national origin. No matter what you look like, it’s your country too.

We’re all capable of making bad choices when we go with a crowd. Be true to your values and try to see things from other points of view.

Everyone can see color, and it’s ok to talk about race and how it affects you. But it’s never okay to be mean to people or make assumptions about people based on their race (including people who share your skin color), gender, or other groups they belong to.

We’re all unique, but we have more in common that we have different. Throughout life, you’ll encounter people who are very different than you; choose to be curious and kind instead of afraid.

We all make mistakes. When you do, apologize and try to make it right. When someone else apologizes and tries to make it right, try to forgive them.

Stay humble. Per Joe Biden’s mom—“Nobody’s better than you, but everyone’s your equal.”

There is more than enough common ground in an egalitarian sense of American morality for us to share with our kids together in their schools, and for any unbridgeable differences in moral perspective, that is what home and Sunday school are for. Progressives already have a solution for living alongside people you disagree with: tolerance. So long as your morals don’t impact my rights, we are good; live and let live.

The structure and salience of systemic racism can be discussed, debated, and dismantled among the adults. Families can expound upon their unique histories and moral traditions at home with their kids. Older kids absolutely should (and already do!) learn about the ugly racist side of American history alongside the inspiring stuff—we don’t need to prescribe colorblindness for everyone or forbid conversations about race. But we also don’t need to teach children that white people have more power (a damaging lesson for children of color, and a self-perpetuating prophesy if there ever was one), whiteness itself is a form of evil, or that America is inherently or uniquely racist. We don’t need to tailor moral guidance to the race of the child being taught, or teach them to adjust their behavior based on their assessment of the race of the person they’re interacting with. We don’t need to conscript kids into the adult culture war. True universal moral truths are simple and apply equally to everyone. If talking to your kids about right and wrong feels complicated, awkward, and hypocritical, you’re probably doing it wrong.

I’ve been reading *Street Gang*, a very comprehensive history of the making of Sesame Street, and I feel like the portrayal of Sesame Street here ignores key parts of the show’s founding and ethos, as well as corrections made early on in reaction to demands from various identity groups.

For starters, the show was intentionally aimed at black children in ghettos. The brownstone and many other elements of the set are intended to reflect areas of NYC that were overwhelmingly minority (Harlem; Bed-Stuy; South Bronx). The popularity of the show, and most of the methods of presentation shroud this: A large majority of the children who loved the show were white, and most of the Muppets (but not all; see below) also coded as white.

Matt Thompson, who originally played Gordon on the show, developed the character of Roosevelt Franklin to directly address this: A wisecracking boy who took to the front of the classroom to teach lessons to his peers. Franklin and the other muppets in his class were similar colors to other Muppets (purple; blue), but their hair and speech patterns coded them as undeniably, and unapologetically, Black. Sometimes the lessons were fairly universal (“if someone hurts your feelings, let them know”; this may be controversial these days), but others would have fit in with Black Power, consciousness-raising lessons of the time, brought to the level of preschoolers: Franklin shows on a map that Africa is much more than jungles (that it is not a country was saved for The Electric Company (jk ;-)).

I fondly remember Roosevelt Franklin, and was surprised to learn from *Street Gang* that he was “cancelled” because of objections from middle-class Blacks that Franklin made them look bad. Looking at the current attempts by Sesame Street to address race, I still don’t understand why they don’t just bring the character back.

[Side note: Chris needs a rewrite on that song:

“I look like caramel!”

“I look like a lion!”

“I look like…a walnut tree. (Sigh)”]

The show certainly was read by the actual people living in poorer, non-white neighborhoods as about them, and in an echo of representational politics today, some demanded the show have them on. Actress Sonia Manzano definitely saw her neighborhood on the show, and got cast as Maria as a result of direct political action from the nascent Hispanic movement (blindsiding the female Black activist who was doing community outreach for the show in Black neighborhoods). The Franklin misstep notwithstanding, the show continued to take time to do things like invite Nina Simone to come on to sing “To Be Young, Gifted And Black”:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=I-f3PYJT5mU

So there’s certainly an approach that Sesame Street can take that doesn’t crumble into mealy-mouthed “colorblindness” but also doesn’t try to place a heavy guilt trip on white toddlers; they already did it 50 years ago!

There is certainly a lot to criticize in the area of racial sensitivity education for children. For my part, though, I've been struck much more by the omission of just plain historical facts from K-12 education. I'm in my mid-50's and grew up in the Midwest. We really did learn just about 4 things about American history in this country concerning our black citizens: slavery, the Civil War, Jim Crow and the KKK and the Civil Rights Movement with MLK. There was absolutely nothing about Black Wall Street, the Great Migration, red lining, let alone anything current (mass incarceration, voter suppression, etc.). I think I would be more sympathetic to the conservative concerns if they could be really honest about how much of the story has been completely untold.