Systems & Starlings & Magnets & Morals

The simple concepts of systems thinking unlock clarifying insights into complex phenomena, like polarization

When I started this blog, I mentioned my enthusiasm for the subject of systems thinking. Systems thinking is a heuristic, a way of observing the world in the hopes of identifying root causes of problems and improving outcomes. As an engineer working on complex mechanical systems, it’s a critical concept in my work, though I was not formally taught it in school. The thing is, you don’t have to be an engineer to benefit from it, because damn near everything is a system.

What is a system?

A few years ago, I helped to develop some formal training at my place of work on the topic of systems thinking. I began the class with a simple question: what is a system? We can think of lots of examples of things we’d refer to as a system: a computer OS, the government, the weather, your immune system… but it can be hard to determine specifically what these things have in common. My favorite, simplest definition of a system is this: a system is a collection of two or more components that interact with each other. That’s it! So, a set of pool balls sitting still on a pool table is arguably not a system, but as soon as one starts moving and hitting the others, they are interacting as a system. The trick about systems is that often, the components in a system are visible, so your tendency is to focus on the components, but what makes a system a system is the interactions, which are often invisible. A prime example of this is a marriage or relationship. You and your partner are two independent beings; if you had never met, you would have never interacted. But now that you’ve paired off, the interactions between you are powerful, and the combination of the two of you is a unique entity different from if you just happened to be strangers on a train sitting side by side. Your interactions have the power to change each of you as individuals. The interactions, though “invisible,” are a critical aspect of the system. It’s what’s truly meant in situations where “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts;” in fact, the whole is the product of the interaction of its parts.

Some systems are rather predictable. You sit on your bike, push the pedal, it moves the chain and your wheels turn. The interactions between the components are so constrained, and the input to the system (your decision about how hard to push the pedal) really only has one variable of concern (force), so the output of the system (speed) can be easily predicted when everything else (weight of the bike and rider, slope of the street) are constant. The interactions have no effects on the components, except you might get stronger through training! A bike designer might want to optimize the way that the parts of the bike interact to improve outcomes (speed-to-force ratio), but there’s not a ton of randomness or complexity involved, and not a lot of room for innovation.

Other systems are extremely complex; one small change to a component or a new interaction has the potential set off an unpredictable series of ripple effects that changes the system forever (as referenced in the concept of “the butterfly effect”). A complex adaptive system is a systems that is both complex and adaptive (ha!). By complex, we mean that there are many, many interactions that are heavily influencing the behavior of the overall system; by adaptive, we mean that the “rules” of the system, the behavior exhibited by individual components (typically sub-systems themselves) in interaction with each other, can change in reaction to stimuli. A classic example of a complex adaptive system is a flock of starlings.

Free from external threat, the starlings’ behavior is rather relaxed: as long as each one is somewhere in the vicinity of another one, they are pretty happy. Once an external threat is introduced, like a predator, an equally simple but far more rigid behavior pattern sets in. Each starling attempts to mirror the average motion of the seven closest birds. As one bird changes its motion, the birds around it change in response on a slight delay, and so on and so on, in an interactive way. This change in the rules of interaction within the system leads to emergent properties at the system level: in this case, murmuration. The birds, as a system, move in an undulating cloud that confuses and evades the predator. The ability to flip a switch and become just part of a bigger system has clear evolutionary advantages. It’s also beautiful to watch. Overall, the motion is still quite unpredictable, but it is more constrained and less chaotic than it was prior to the introduction of the threat. It is a behavior that is not possible in a simple collection of components; they must form a system through interactions in order for the behavior to emerge.

Humans as systems, in systems of humans

It should come as no surprise that any time humans are interacting, we have a complex adaptive system on our hands. Examples of systems of humans include a couple, a group of friends, a family, a city, a church, a sports team, a company, a school, a political party, a country, a group of cars on a highway, and on and on. Any time a human is interacting with other humans, they have the ability to change their behavior in response to what is happening in the rest of the system, and emergent properties can occur.

Humans themselves are systems, of course. I tend to think of human psychology somewhat like computers: for most of us, some of our traits seem to be “hard-wired” in our genes through evolution (nature), and other things “coded” into us through our upbringing (nurture). The hard-wiring can only change through generations and generations of reproductive evolution, but the coding can change at any moment. The things coded into us at an earlier age seem a lot harder to overwrite than things we pick up later. The most effective coding seems to tap into the hard-wired traits in most neurotypical humans. [Note, at this point, I’m out of my depth from a formal education standpoint, so I welcome diverging views.] For something to be a result of human DNA, it would have to be nearly universal; not necessarily in every single human, but at least prevalent in every culture around the world. Most of us have the ability to feel something akin to disgust, fear, joy, anger, and sadness. We intuitively feel some things are “right” while others are “wrong,” though what triggers those feelings varies widely. We generally to want to form communities, to team up with others to support each other against the elements and enemies, and we form extremely close bonds with friends or family. We have the ability to empathize with others, and we usually care how we’re perceived by people in our tribe. We have a sense of dignity or pride, and a powerful hunger for it to be fed either by our interpretation of external evaluation (human or divine) or our own internal validation (self-esteem). Most of us find fulfillment in overcoming challenges, and once our basic needs are met, we will even create challenges for ourselves (like training for a race or angling for a promotion) to avoid the listless, unmoored feeling of having nothing to work towards. We often want to be part of something bigger than ourselves, to be with other humans to experience emotions or accomplish goals together in a transcendent way. On the whole, most of these capacities have evolutionary benefits for our group, rewarding us for teaming up and problem-solving together. However they can also have the capacity to trigger addiction in individuals, leading us to sometimes ignore long-term penalties for short-term benefits, or forgo the needs of a larger community for the gain of ourselves, our immediate family, or smaller community.

Our “coding” can also be thought of as our culture. It’s the morals, values, traditions, rules, or laws we are taught throughout our lives. Sharing these “rules” with others can help us bond in a community. Receiving validation from people we admire, or even just imagining that they would approve of our behavior (in the case of deities, celebrities, or the ‘cool kids’), can boost our pride and reinforce our behavior. Seeing others violate deeply-held moral codes can trigger anger, disgust, or offense. When people we hold in high regard appear to judge us for failing to live up to our shared moral code, we feel deep shame, which often motivates us to change our behavior and even update our “coding.” Alternatively, it can lead us to reject the person or people passing judgement, and break off and find a new community whose values are closer to our own. These codes are not genetic, and as such, they can evolve much more quickly than hard-wired traits. Within a single person’s lifetime, their morals can change dramatically, as they interact in new ways with new people who themselves are rapidly changing their behavior. Encountering someone from a different culture abiding by a different set of “rules” can set off all sorts of emotions—curiosity, fear, disgust, introspection. In the modern era, humans encounter humans from other communities at a speed and scale never before known in history; the “culture wars” might just be a completely inevitable result.

Magnets and morals

Returning to the concept of complex adaptive systems, another example of emergent properties from the world of science is magnetism. Each atom is itself a system of neutrons, protons, and electrons. When the electrons spin in opposite directions in equal numbers, the atom is neutral. But when a ferromagnetic or paramagnetic atom enters an electric field, the electrons can all begin to spin in the same direction, creating a positive and negative pole for the atom. The atom rotates itself to match the polarized orientation of the atoms around it. When many magnetized atoms come together, the emergent magnetic force they exert grows stronger. When the magnetized material encounters another magnet in the same orientation, they attract to each other and form a single, larger unit. However, when it encounters a magnet oriented in the opposite direction, the forces repel each other.

Lately, I’ve been thinking of morals and morality in the same way. When a person is a part of a community, the orientation of the broader community exerts a strong force on the person to align their perspectives, beliefs, and morals with others who they admire. The more people who hold the same views come together, the stronger those views become. Over time, preferences become beliefs (“I’m a Saints fan” becomes “The Saints are the greatest NFL team of all time”), and beliefs become morals (“Falcons fans are the scum of the Earth”). A moral has the power to re-orient other perspectives. It has a very strong polar orientation: there is a right, and there is a wrong. There’s no “agree to disagree;” if you disagree with me, you are immoral, and I feel a visceral urge to either reform you or repel you. Align with my polarization or get away from me. Encountering someone with a different moral orientation can in rare instances lead to some soul searching, but more often than not, it leads to a strengthening of one’s original orientation, or even slight adjustment to be even more in opposition to the threat.

As with the starlings, this emergent property of humans surely serves an evolutionary purpose! When humans in a group share values and morals, they are all “on the same page.” It’s easier to build trust and eliminate fear, because your behavior will be relatively predictable for others. We can take on great challenges together with discomfort out of the way; we can start a family, build a society, or go to the moon. Throughout human history, moral communities have started, grown, and died away. They have merged, divided, or clashed. In this way, moral systems have also undergone a “survival of the fittest”-type influence; almost all common moral themes seem to have some way in which they would or did help a group flourish, though sometimes tragically at the expense of other groups or minorities within the group. Over the millennia, it seems some frameworks provide stronger foundations for flourishing than others, though it does seem humans are bound and determined to re-learn the lessons of the past over and over again. Many of us always want to fiddle with the dials and see if we can make things better; in fact, for many of us, it’s a moral imperative itself.

Polarized American Morality

In Why We’re Polarized, Ezra Klein makes a strong case that our news media and social media diet has led many of us to take on one of two, nationalized, mega-identities: conservative or progressive. In the past, these identities were not so binary, and people had other, stronger, cross-cutting identities like their churches, their sports leagues, their companies, or their local community; national politics was not nearly as much of a “hobby” as it is now, and people had less opportunities to learn about it, discuss it, form opinions, and be exposed to those with different opinions. As people became more polarized, so did the political parties, creating a feedback loop that exerts a powerful magnetic force that compels most Americans to “pick a side.” Those of us who’ve managed to break free of that binary force field often feel lost and disconnected, seeking out others who are similarly adrift and attempting to form new strong opinions we can all agree on to bring us together (welcome to Substack!).

It can be hard to break the moral mental forcefield and look at policy positions or opinion pieces without having a visceral, “Is this a good guy or a bad guy? Do I agree or am I offended?” reaction. Often, we see a claim that does not 100% align with our personal moral truth, and we take it to mean that this person feels the opposite of us, which would be immoral. At the risk of triggering this feeling in you, dear reader, I want to lay out a brief list of what I see as the key moral “truths” for each of our national mega-tribes, best as I can steelman them. I am not agreeing or disagreeing with any of them (yet), nor am I passing judgement on any of them as helpful or harmful. But just seeing them all laid out is a key step in deciphering when and why people are triggered.

For most of us, reading one of these columns will elicit a head nod or maybe even a fist pump, while reading the other will stir up feelings of anger, offense, or an urge to argue. I think it’s important to acknowledge that this is true for both camps. When we hear someone from the other camp get offended, we want to brush them off as overreacting; when they argue, we want to bury them with our superior logic. But the mirrored responses should allow us to actually empathize instead; they are reacting the same way we would. They feel just as deeply and sincerely about these things as we do. They are motivated by a chain of logic that would, in some way, bring benefits to the group if adopted broadly, though negative impacts are often downplayed or ignored. Each of us is motivated to see the good in our own perspective and the danger in the other.

There are some who claim some people are genetically predisposed to fall in to one of these categories or the other, based on their “openness” or “conscientiousness.” My intuition says that’s mostly hooey. Polarized moral alignment seems far more explainable to me as an emergent property of being in a group. Those who cling to genetic explanations also seem to have a hard time seeing why anyone would choose to adopt such backward or anarchist views as they have on the other side; they must be defective! But as a self-regulating system, it makes sense that a society might split into two groups; one that wants to change things and one that wants to keep them as they are. A gas pedal and a brake. If one side gets too powerful, people in the middle will switch sides to regulate the speed and direction of social change. Team Gas Pedal is motivated to see everywhere we could be doing more, doing better. Team Brake is motivated to see the benefits of the way things are now, or were in the past. Working together, these two teams would be a powerful organizing framework for optimizing the total system of society. Unfortunately, we’ve forgotten how to work together. Instead of the elegant, seamless transition of gas, brake, gas, brake, each team seems determined to stomp on their pedal as hard as possible and cause the car to lurch all over the place until it falls apart.

The truth is in the combination

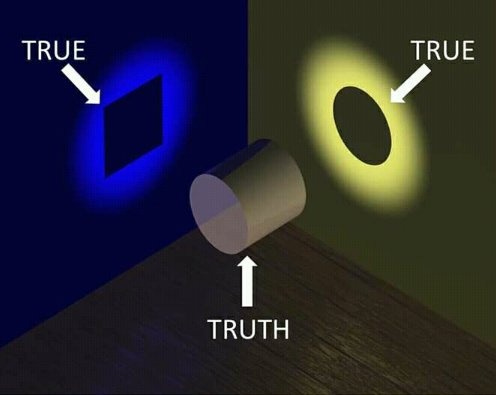

Another tenet of systems thinking is the value of perspectives. In a complex, multi-variate system, many perspectives are needed to understand reality. This graphic is seared in my mind:

In our national politics, we used to have one side arguing on behalf of the square and the other on behalf of the circle, and they would figure out a way to make a plan together. Now we have moralized these perspectives. If I care about the square, and the square is right or the truth (not just “true”), I may find even a mention of the circle to be immoral and offensive. Attempts to even discuss the circle are a denial of the square, and therefore a denigration of me as a person, as my personal identity is wrapped up in my beliefs about the squareness of the world. The perception of the circle people as an external threat leads me to strengthen my alignment with the squares and dial up the moral force field. Each side is making the other side more extreme. Views that were just preferences or beliefs a generation ago have turned into morals.

For those of us who, like me, lean progressive, this is not a good place to be as a society. If I am deeply offended at even the utterance of a view dissimilar to mine, I cannot learn anything from it. If no one is collaborating, old patterns will perpetuate unchecked, and the state of things will stay stagnant or worsen. If we want society to be able to function and continually improve, we have to learn to drive the car together. Those of us who want to hit the gas have to learn the value of the brake—it could prevent us from driving right off a cliff.

Im going to assign my 15-year old daughter to read this. That circle square analogy blew me away.

I’ve always been blessed to be a counter-intuitive thinker. I can’t help but question every point of view from the other side.

I’ve found my greatest strength in dealing with polarization is not caring. Once you accept that people are flawed. That good people can have horrible ideas, it’s easier to avoid outrage.

I have never really gotten upset over a Presidential election. I’ve come to the conclusion that in two alternate universes, anyone individual daily lives would be virtually indistinguishable, with perhaps the exception of wars. And wars seem to happen independent of political leanings. Obama vs Trump for example.

Anyway, I hate that I know you are this smart. Takes the wind out of my sails for my substack.

I just started reading _High Conflict_ by Amanda Ripley -- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/book-excerpt-high-conflict-by-amanda-ripley/ -- which has a lot of overlap with this post.

It's tries to explore what she calls "high conflict" (in which the conflict becomes self-sustaining, and hooks people into interpreting everything in the context of the conflict) from good conflict which allows for the possibility of resolution.

I'd recommend the book. It's well written, very readable, and built around a number of memorable stories.

It's an ambitious topic, and I don't think it is completely successful in offering an explanatory framework and it sometimes flatters the reader a little too much (by implying that the reader is so much smarter than the people stuck in high conflict) but those are quibbles. I think it goes very well with this post.