The missing mothers and the trade-offs of inclusion

Feeling left out hurts, but sometimes focus is needed

As I write this post, it’s Mother’s Day. I’ve had a lovely, low-key day with my son, who unfortunately has a poorly-timed stomach bug but is otherwise as sweet and entertaining as usual. On his behalf, my husband got me flowers, candy, and muffins for breakfast. But Mother’s Day wasn’t always this mellow for me. I briefly mentioned in my last post that I was going through some personal health issues in 2017. In fact, my husband and I were four years into a battle with infertility.

We got married in the fall of 2012 and by Mother’s Day 2013, we were trying to start a family. That Mother’s Day was spent entertaining daydreams of being able to celebrate with a baby in my arms the following year. Over the months, the excitement gave way to nerves, unease, dread. Mother’s Day 2014 was a mix of denial, jealously, and despondence. It was clear by then that becoming parents wouldn’t be as easy for us as it seemed to be for everyone else, but we weren’t ready to admit to ourselves that it was going to require extensive medical intervention. We began pursuing medical help later that year; by Mother’s Day 2015, I was likely officially depressed, though I never saw a mental health professional. Life felt like it was on indefinite pause.

By Mother’s Day 2016, we had started to see a reproductive endocrinologist and were getting ready for a few rounds of IUI, which turned out to be unsuccessful. In the fall of 2016 we began IVF and finally, finally, after three and a half years of trying, I was pregnant. It felt incredible. The clouds lifted and I finally felt like someone had pressed “play” on life again. I remember November 2, 2016—we were finally going to have a baby, the first female president was about to be elected, and the Cubs had won the World Series. Life was perfect. Then, two weeks after Donald Trump was elected president, we learned it was a miscarriage. It felt like a cruel joke. We felt humiliated as we called the friends and family who we’d told “too soon” that in fact we’d lost the baby. I felt like I’d been a fool to ever think this would work out for us.

Mother’s Day 2017 was the worst. In the aftermath of the miscarriage, our doctor recommended we try genetic testing on our embryos to improve our odds. We did another round of IVF to get more embryos to test, and we transferred one of the good ones. In April 2017, I was pregnant again, daring to let myself feel optimistic. But within a week of the positive test, it was another loss. My Facebook feed was full of friends who were on their second or third child, basking in the Mother’s Day glow, reflecting on how it was all “hard but worth it,” and I felt like life was passing me by. In a way, the struggle to figure this puzzle out, beat the science, was one of the only things that kept me going. By the fall of 2017, we were trying another IVF transfer, which led to a third miscarriage.

In my darkest moments, there was nothing that didn’t trigger my sadness. Obviously babies and children would depress me. I sat in the infertility clinic that we’d spent way too many hours in, staring at the photos of “success story” babies all over the wall, remembering how they used to give me hope but now just pissed me off. Sometimes I would pass an adult stranger on the sidewalk and think, that person was once a baby, and that means someone else was able to get pregnant and give birth to them. I’d look around the grocery store or a stadium full of people and realize every single one of these assholes was the result of a basic biological process I couldn’t get right. Fucking hell.

Now, I pride myself on seeing the bright side and giving myself my own psychological pep talks. I tried to channel my love of kids and my desire to be be a mom into other things. I continued to volunteer as a Girl Scout leader, something I loved and did for 10 years. I found fun ways to connect with my nieces and nephews. I was active on infertility support message boards, sharing what I’d learned with other women and forming virtual friendships. I reminded myself of all of the fantastic, inspiring women I knew who chose not to be mothers. More than anything, it was actually very comforting to reframe things for myself and remember that a fulfilling life did not require being a mother. Yes, it was what I’d always wanted—a precocious big sister who had to be told “not the momma” by her parents from age six—but it wasn’t the only way to enjoy life and leave the world a better place. I determined that if I eventually had children, fantastic, but I was going to seize life by the horns either way—my self-worth was independent of my reproductive abilities.

On Valentine’s Day 2018, we transferred our last “good” embryo. We did not know what would happen, but we knew if it didn’t work out, we had some big decisions ahead of us. Would we go through yet another round of IVF? Would we pursue fostering or adoption, which often came with their own heartbreaks? I tried not to guess about the future too much. Guessing might accidentally lead to hope which always led to pain. Like the three previous embryo transfers, this one stuck—that part of the process never seemed to have an issue. Having been through the fire before, we never let ourselves be any more optimistic than “so far, so good.” Every doctor’s visit was a small hurdle to pass. After a few months, we were transferred from the infertility clinic to a normal OB/GYN, where we were treated as strangely un-special. On Mother’s Day 2018, when I was 14 weeks pregnant, we let my mom know she would be a grandma again (like, 98.6% likely). It almost felt reckless. We still held our breath through every doctor’s visit, all the way until the day we went to the hospital and our son was born and in our arms.

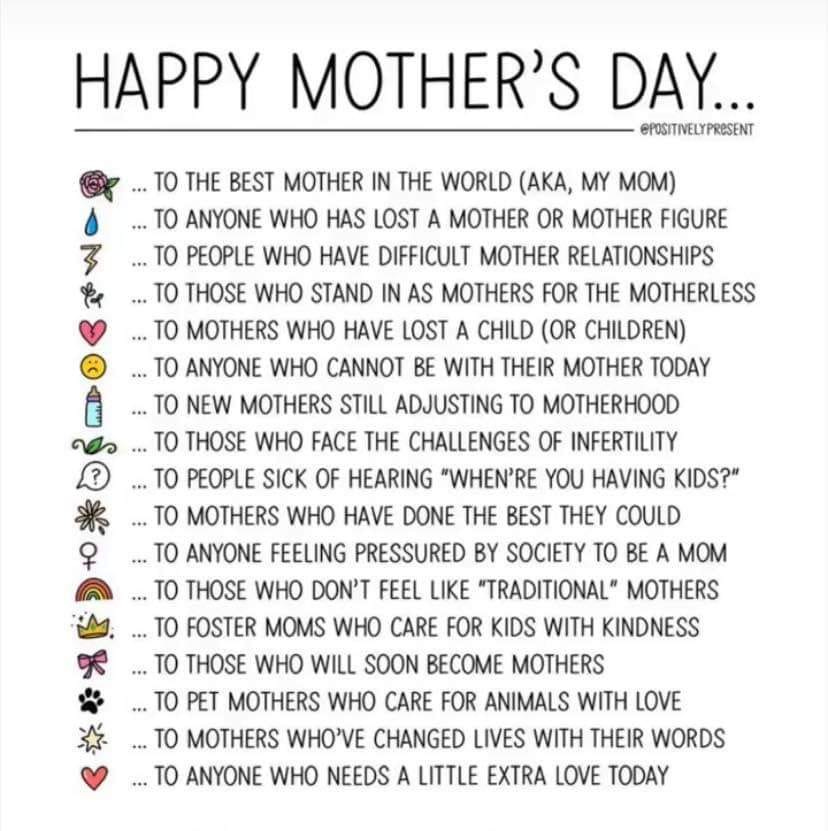

On one of those dark Mother’s Days, I came across an image similar to this one. It made me feel “seen.” An acknowledgement that Mother’s Day isn’t all laughter and brunch and greeting cards for everyone. A reminder that I was far from the only one feeling a complicated mix of feelings on this day. At its best, this is what “inclusion” is about. It means pausing and taking the time to pull people in who are otherwise feeling left out. When the right message comes at the right moment from the right person, it can really make a difference in someone’s life. And to the bystanders, it can really reframe the way they see the world. Someone without complicated feelings about Mother’s Day might read that post and think of someone else in their life who might be having a complicated day, and reach out to say hi.

The sad truth is, though, that absolute inclusion is an impossible goal. Human life is complex and fraught. Everyone, every day, is going through their own struggles. It is nice to be remembered, to be acknowledged, to be “seen.” It makes sense to rely on those closest to us to do this work, and to do this work for those closest to us. But being seen does not erase the pain. And when the pain is deep enough, all-consuming enough, it will find its own ways to make things worse. It will see strangers being happy and say, “Fuck them. Who the fuck do they think they are, being happy?” It will seek out something, someone to blame. I once read, “Just because you are feeling pain does not mean someone has hurt you.” Undeniably true, but hard to remember in the depths of depression.

Mother’s Day is a celebration of the women for whom being a parent is a major aspect of their lives and their identities. It is an acknowledgement of the degree of hard work that usually comes with the gig. For most mothers, being a mother is indeed a significant part of their identity. When I think about “identity,” I think about what you would answer if someone asked you to describe yourself in 5 words or phrases. It’s your essence, your idea of yourself, what you hope others see and acknowledge about you, providing external validation (when you “feel seen”). It’s a source of pride and dignity. Unfortunately, it seems nearly inevitable that for someone feeling pain or insecurity about their own identity, or feeling like they’re “not enough,” they will often feel hurt, excluded, or threatened by a recognition of someone else’s identity. With motherhood being as sensitive of a subject as it is, a celebration of mothers is always going to be a source of pain for many.

On the one hand, I think it’s admirable when people see this happening and take the time to reach out a hand and provide support for those who are struggling, especially in a personal way to people they actually know. On the other, it seems inevitable that if we spend any time drawing attention to anything that doesn’t include us all, someone will feel hurt and left out. Those who are inclined to include feel like it’s a matter of basic human decency to take the time to acknowledge those on the margins. But the wider the spotlight, the weaker the focus. Those who are skeptical of what feels like a moral obligation to include everyone find the constant exception-taking to be tiresome and performative. What’s the right thing to do?

The latest culture war kerfuffle this weekend is about “birthing people.” Last week, Rep. Cori Bush gave powerful, personal, emotional testimony before the House Oversight committee in a hearing on “Birthing While Black: Examining America's Black Maternal Health Crisis.” The video is only 3.5 minutes long—just watch it.

My suspicion is that the vast majority of people getting worked up about “birthing people” did not actually watch the video. They saw a tweet, a counter-tweet, a joke, an article railing against woke excess, and they jumped on the wagon. “Happy Birthing Person’s Day!” To be honest, I did a little at first too. Until I actually watched the video. After watching it, I don’t see how anyone with a soul can come away feeling like she tried to “erase mothers.” She does not dehumanize women and relegate them to their birthing functions. Quite the opposite. She tells a deeply personal, vulnerable story. She tells a story that should make anyone outraged along with her. She speaks explicitly on behalf of black mothers. Yes, in one sentence in a three-and-a-half minute speech, she mentioned “birthing people.” It was a single phrase meant to nod at both surrogates and non-binary people who give birth who might not feel like they were covered by the word “mother,” but would in fact be covered by the legislation under consideration. But it was hardly the centerpiece of her speech.

Her speech was meant to draw attention to some pretty startling statistics. The opening statements of the hearing cut to the point:

"Across the globe, our maternal mortality rate ranks the absolute worst among similar developed nations and 55th overall. … The danger of giving birth in the U.S. is not equally distributed," [Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-N.Y.)] continued. "The CDC estimates that Black women are more than three times as likely to die during or after childbirth as white women. Black Americans experience higher rates of life-threatening complications at every stage of childbirth, from pregnancy to postpartum. It doesn't have to be that way; CDC estimates 60% of these deaths are preventable."

To understand the problem, "we have to take the blinders off our history and acknowledge that our healthcare system, including reproductive healthcare, was built on a legacy of systemic racism and mistreatment of Black people, and that legacy continues today," she added.

Rep. James Comer (R-Ky.), the committee's ranking member, agreed. "Maternal mortality for Black women is 2.5 times the rate for white women and three times the rate for Hispanic women," he said. "We all agree that is unacceptable. The United States is one of the most advanced healthcare systems in the world, and we can and should have lower mortality rates. There are a range of factors contributing to this process, from lack of access to proper care to maternal mental health crises, which take the lives of so many mothers."

Here we have rare, precious, bipartisan agreement that American maternal death rates, and the racial disparities within them, are unacceptable. Bipartisan agreement, if only for a moment, that we need better research into the root causes. People of all races and both political parties trying to work together to save lives. And what makes the headlines? “Birthing people.”

I understand how it happened. To most people, it came out of far-left field. It was distracting to say the least. It was surprising in the speech but downright jarring in the tweet. It’s hard to say if the hearing would have gotten much attention at all if these two words hadn’t drawn ire, and therefore a defensive response. It was an attempt to be inclusive, and I believe it was sincere. But, inevitably, expanding the spotlight weakens the focus; in this case, the spotlight moved entirely to discussions of woke excess and the alleged erasure of mothers. I am not going to guess whether Rep. Bush, Rep. Pressley (who also referred to “birthing people” in a tweet), or their staffs would do it differently if they could do it again. I suspect they are somewhat energized by the fight. But I am sure they would rather be making real progress on saving lives of women and infants of all races.

The discussion of disparate maternal and infant mortality rates won’t be straightforward. There will be plenty enough controversy there. The hearing included gut-wrenching, heartbreaking, personal stories of loss. Witnesses called by Democrats tended to focus on the racial biases of white doctors. Republican Reps. Gibb and Clyde countered that poverty could be at play, and brought up that low-income white women also die at high rates. The data is not always clear, but in this area it is—solid studies indicate that racial disparities persist or even worsen when income, educational status, or mother’s age is accounted for. There is certainly still work to be done. There are certainly many, many factors at play. But if there were ever a time to set aside our tribal soldier mindsets and try to be scouts, it’s when the lives of mothers and babies are at stake.

I know the pain of feeling left out. I also know the pain of losing a pregnancy. In an ideal world, no one would have to choose which of those two pains to care more about mitigating for others. But someone needs to put down their swords first in the culture war if we’re going to collaborate and make progress on something critical like this. I can’t speak for everyone, but I suspect most pregnant people would accept passively being referred to as mothers if it meant greater protection of their health and their baby’s health. Tens of thousands of mothers are missing this Mother’s Day due to preventable deaths. Let’s focus on fighting that instead of each other.

A few extra thoughts rattling around my head in the night...

1) This piece was a little more stream-of-consciousness than usual. The details of the first half weren't strictly needed to make a point; I just felt like sharing today. Also I meant to include that I was 29 when we first started trying for kids. I know many people assume most people who have to resort to IVF just waited too long. I don't believe that was the case for us, nor was it the case for several of my close friends who also had to go that route.

2) I missed the chance to point out one of the most obvious inclusion trade-off related to the hearings. They chose to focus on black mothers. This was an *exclusive* move--they chose not to include mothers of other races. You could argue this was the right or the wrong thing to do, but it undeniably allowed for the effort to focus on the unique factors affecting black moms, of which there are many. Personally, I don't begrudge them the lack of inclusion here (though from a "race-class narrative" perspective, it could arguably be a missed opportunity for coalition-building, since the laws being discussed would help all women). But regardless, it does make implication of "inclusion is always a good thing" come across as a bit hypocritical. Sometimes focus is needed.

I’m writing this without having read your appendix!

It struck me that there’s more than enough blame to go around on the Congressional issue you cite at the end. The members using the phrase “birthing person” could have avoided it entirely or couched it in a less provocative way. It’s pretty easy to predict that people outside your tribe might find it jarring, so much so that future conversations might be shut down before they even start.

The conservative cranks could have made a joking reference and then gone on to engage with the substance of the other side’s position. And thus forward movement goes on!

Finally, as the father to two highly irritating supposedly adult children I must say that I frequently forget how fortunate we are that they’re in the world and doing well.